Japan 2017

Monday, March 5, 2018 at 10:07AM

Monday, March 5, 2018 at 10:07AM

JAPAN

Our hike in Japan has given us one more item to add to the “Tips and Warnings” section of this website: Do not confuse a “hike” with a “pilgrimage,” especially when said pilgrimage has been designed for people without the proper religious bona fides who will be using a bus to get from temple to temple, instead of their own feet. Beyond that, check weather records for as far back as possible, to get a realistic idea of whether you can expect the rain to let up for even a few hours. We were seduced by two words: “hike” and “Japan”; we were looking for the former, and had fond memories of the latter, having spent some happy hours in the Business Class lounge in Narita Airport. Calculating that we had amassed enough frequent flyer miles to gain entry into it again, we eagerly signed on.

Our meeting point was the very convenient Kansai Airport Hotel. Kansai International Airport, Japan's third busiest, was built in 1994 on a man-made island in Kansai Bay. The island's features consist of: one airport, one train station, one shopping mall, and that one hotel. After introductions with our group, guide and driver, we assembled for the traditional Welcome Dinner and were given an outline of what lay ahead. We would be following sections of a pilgrimage route first walked by the Buddhist monk, Kobo Daishi. Born on the island of Shikoku in 774, Kobo Daishi was a hugely talented scholar, artist and poet. He studied Buddhism in China before returning to Japan to found the Shingon School of Japanese Buddhism in 805.

Kobo Daishi

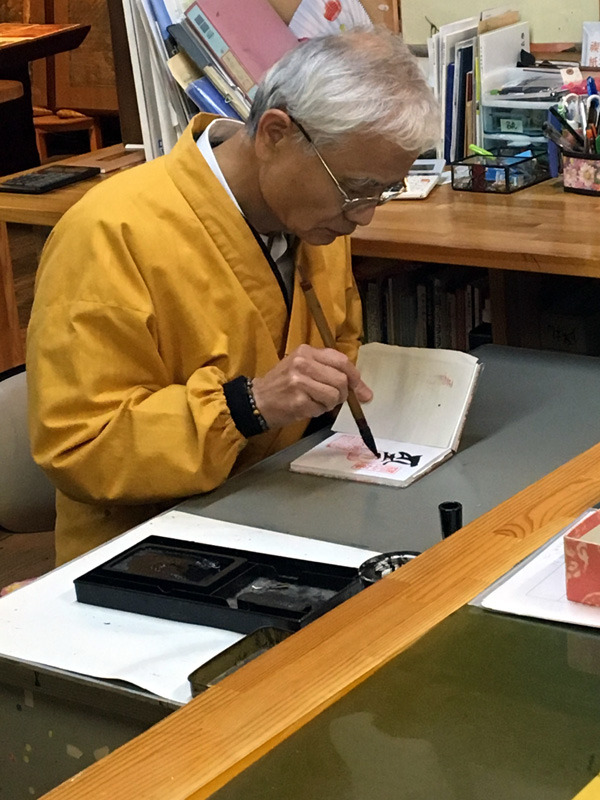

The pilgrimage consists of 88 temples, and the traditional way to visit them all is, of course, on foot, emulating Kobo Daishi himself. Those doing it that way take between five and seven weeks to complete the 750 mile circuit, and are distinctively outfitted in white coats and conical straw hats, carrying the long walking sticks that identify them as pilgrims. Many have satchels containing the books that will be stamped at each of the temples visited. We were never mistaken for real pilgrims, but tried to follow the guidelines for respectful behavior wherever we went.

Our first stop was Koyasan, world headquarters of the Shingon sect of Japanese Buddhism. Kongobu-ji (the suffix “ji” denotes “temple”) is the primary temple of Shingon Buddhism, and many pilgrims begin their journey here so that they may ask for Kobo Daishi's support before setting out on the circuit. A number of people in our group bought temple seal books (nokyocho), and at every temple we visited there was a calligrapher ready with a brush to insert the seal of that particular temple in the book. For a price, of course. It becomes either an increasingly expensive souvenir or else a possession or great spiritual value, depending on the owner. Some Japanese ask to have their nokyocho buried with them.

Later we walked through the enormous Okuno-in Cemetery, the largest in Japan. The rain, now coming down in buckets, added to the somber gloom surrounding the graves and memorials to feudal lords and deceased luminaries, but didn't make us eager to linger. And that was a shame; the carvings and statues, some recent and some centuries old, were beautiful but unintelligible, to us.

Okuno Cemetery courtesy M.Koberda

Okuno Cemetery courtesy M.Koberda

That night we stayed in a monastery. This proved to be more romantic in anticipation than in reality. The first hurdle was Japanese footwear protocol, which we were to run into wherever we stayed. Your own shoes come off at the outer entrance way. Slippers are provided to get you a little further in, and these are perhaps the most dangerous thing about hiking in Japan. They seldom fit well, of course, and attempting to keep them on while climbing up or down stairs is impossible. They must be abandoned before stepping onto the delicate tatami mats that cover most bedroom floors. The Japanese are proud of their full-employment status, and it appears that they help to maintain it by positioning minders at every hallway corner to make sure you are conforming. (We took to sneaking around in our socks, but we felt like criminals.) Yet another pair of slippers is to be worn in, and only in, the bathroom, and left there when exiting. We seldom got that right, and have doubtless left many a damaged bedroom tatami mat in our wake. An added attraction of the monastery we were staying in was the fact that the bedrooms were in a separate building, across a cobbled courtyard that had to be navigated in yet another kind of footwear, that didn't fit, and hadn't been designed for cobblestones. In, it goes without saying, a downpour.

Our bedroom was spotlessly clean but spartan. A plastic thermos of hot water had been thoughtfully placed on the one, very low, table in the middle of the room, for those who couldn't wait another minute for a cup of green tea. That wasn't top of our list, so to kill time in an environment that valued spirituality above alcohol, we went to hear a monk chanting interminably in what was billed as a “meditation,” elsewhere in the monastery.

Dinner that night had a lot of our hopes riding on it. We had accepted that it would be vegan, of course, but read into that “healthy and aesthetically pleasing.” What we had not taken into account was that we would be kneeling throughout the entirety of it. We both discovered that knees as old as ours don't enjoy kneeling and that we are physiologically unable to sit cross-legged for more than a minute or two. The only option remaining was to stick both legs out into the face and dishes of the person opposite, or just stand up – the worst imaginable way to lose face in a country that doesn't believe in losing face.

Various Awkward Positions at our Monastery MealWhile we were tackling our dinner as best we could, our bedroom had been tidied up and transformed. The table had been moved to one side and two futons now occupied most of the floor space. The communal bathroom was a floor below, but since getting into an upright position off the futon was already a struggle, we only hoped we wouldn't need it. We awoke the next morning to find ourselves still jet-lagged, still on the floor, still listening to the rain pouring down outside, and even more arthritic than we had been when we went to bed. And all of this in a part of the world that doesn't understand the word “coffee.” Breakfast was another kneel-on-the-floor-in-front-of-unidentifiable-food experience, but the coffee problem was quickly solved by our guide. He confirmed that there would be none inside the monastery, but led the way to a vending machine on the road beyond the gate, and there it was - piping hot in a can too hot to hold. Never tasted better!

A two-hour ferry crossing took us to the island of Shikoku, where all 88 temples of the pilgrimage are located. We had an exquisite looking Bento Box lunch on the ferry. Before being deposited at our hotel in the center of Tokushima we walked to three of them: Ryozen-ji (Temple 1), Gokuraku-ji, (Temple 2), and Konsen-ji (Temple 3). Since dinner was on our own that night and our hotel adjoined a large shopping mall, we made a determined and ultimately successful search for food that we recognized: pizza. And to top that off we stocked up on lifesaving provisions at a Seven Eleven conveniently near the hotel. You can't be too careful.

The next day we walked to the mountaintop Temple 20, Kakurin-ji, also known as the Crane Forest Temple. Then it was steeply down and up again to Temple 21, Tairyo-ji, the Great Dragon Temple, on the far side of the valley. It was a lot of walking with a substantial amount of elevation, in the pouring rain, and we were glad to pile into our bus for the long drive through the Iya valley to our remote hotel.

There are hopes that the Iya valley can be developed as a tourist destination, but that hasn't happened yet. We drove through deserted villages; whatever livelihood they once offered had long since disappeared, along with the inhabitants. It was Appalachia without that same sense of prosperity. The road was narrow, with one hairpin bend after another, but convex mirrors at every turn warned of oncoming traffic, of which there was very little. Even when two vehicles did meet, there appeared to be an accepted protocol that dictated which one should back up, and the drivers always saluted each other politely as they passed. We did not see one traffic altercation during the trip.

Iya Valley courtesy of M.Koberda

Iya Valley courtesy of M.Koberda

We were given a warm welcome when we finally arrived at our hotel, and soon found ourselves facing another Japanese meal of tiny dishes, tiny portions, little hot pots, and seemingly endless courses. There were many attentive kimono-clad woman hovering nearby, monitoring our every move and correcting all our many faux pas as soon as we made them. Since they had little or no English, the menu remained largely impenetrable. Among the recognizable offerings were miso soup, rice, ginkgo beans on toothpicks, persimmons, and green tea pudding. New taste sensations were yuzu fruit palate cleansers (good) and whole fish, head and tail included, skewered on a chopstick (bad).

We were to have many of these multi-course meals over the course of the trip. Kaiseki ryori are considered to be the pinnacle of Japanese cuisine, and the cost (anywhere up to $350 per person) reflects that. There may be as many as fifteen courses, very small, often raw, and very aesthetically served. So the lack of appreciation on our part simply shows us up as the philistines we are.

Unidentifiable and Irresistible Delicacies Kept Coming

Unidentifiable and Irresistible Delicacies Kept Coming

We woke the next morning to the sight of fog coming in through the mountains. Of course it soon gave way to rain, but it was beautiful while it lasted. We drove back down the Oboke Gorge, getting a better sense of it than we had in the dark the night before. The road followed the course of the Yoshino-gawa, Shikoku's second longest river. Thick cedar forests covered the sides of the mountains, with trunks so straight and long that it was impossible to see their bottoms. Even in the daytime there were no signs of life in any of the villages we drove through. It was a very different scene during the civil wars of the 12th century, when the rival Heike and Genji warriors were vying for supremacy in one of Japan's greatest battles. “Vine” bridges across the gorge were a preferred tactic because they could either be hacked down, or, if dry enough, set on fire to prevent pursuit. Of the many that were once there, only two remain, both substantially reinforced now that warring clans no longer need them. Still, given the painstaking work involved, having to choose between hacking the bridge to pieces or being hacked to pieces oneself must have been a tough choice for any loyal warrior.

The highlight of the day was to be the summit of Shikoku's highest peak, Tsurugi-san (6,412 feet) Three licensed mountain guides awaiting us in the parking lot made the prospect seem more daunting than it was. The climb itself, what there was of it, was negligible because a unique chairlift hauled us up to within one hour of the summit. The lift was unique in the sense that the single seats had no safety bars, but one was never more than 8 feet above the ground. There is no way to know whether the wind would have been even fiercer had we been higher off the ground, but it was bad enough where we were, and combined with the rain and increasing cold as we ascended, it made the ten minute ride feel like an eternity. Some in our group bailed out at the bottom of the lift. Others were sorely tempted to leap out from their chairs along the way because it looked perfectly safe, and far preferable to sitting passively awaiting hypothermia. The top of the chairlift wasn't quite the top of the mountain, but a walkway of planks had been constructed to lead to the “view point.” (We use the term derisively.) The few photographs we took show wet, chilled hikers attempting to stand upright and smile in the teeth of the gale. The most memorable part of the climb was the mountain guides' insistence that we visit the rest rooms because they were “very, very beautiful.” And they were; Toto toilets, with all their thorough and up-to-the-minute features!

"View" Point from Shikoku's Highest Peak

On our way back to our hotel we stopped in Nagoro, a quiet village of about 35 living souls and ten times that many scarecrows. They are the work of Tsukimi Ayano, who grew up in the village and made her first scarecrow to be a genuine crow scarer; she had planted some seeds and hoped a scarecrow with the likeness of her father would keep the birds away. From that has grown a remarkable collection of “people” in various everyday situations, some humorous, some poignant, some downright startling, hiding in corners where one least expects to see them.

We spent most of the next day in our bus, driving around the southern coast of Shikoku. There was one stop at Kongofuku-ji, Temple 38, and good scenery, but the highlight for us was ending up at a large spa-like hotel, offering multitudes of amenities, including a bar that served everything imaginable - except wine.

The next morning we reluctantly tore ourselves away from the actual beds and normal height tables in our spacious spa room and continued the drive, now along the western coast of Shikoku. There was a stop at the Taga-Jinja Fertility Shrine. It would have been more accurately named the Pornography Temple: three floors of erotica collected by one eccentric man, who, either despite his predilection or because of it, is held in very high regard in the area. Almost all the women in the group were through the “temple” and out into the open courtyard as fast as possible, but the men lingered a bit longer. It had a gift shop offering predictably-shaped items that would have been fun to give but difficult to gift wrap.

Entrance to Taga-Jinja Fertility Shrine

Entrance to Taga-Jinja Fertility Shrine

By now, thanks to the Internet and communications from home, we had gleaned that Typhoon Lan, dubbed a “monster typhoon,” was gathering its forces and had us in its flight plan. Our guide asked us not to discuss it among ourselves, lest we frighten each other, and at one point he brushed aside our queries about a siren that we heard, dismissing it “as just a police car, or something.” (Only as we were saying our goodbyes on the last day did he reluctantly admit that it had indeed been a typhoon warning.) For a few hours Lan was poised to make landfall just a few miles from where we were, but in the unpredictable ways of typhoons and hurricanes, the eye swept past to the east of us, giving us only a day or two of lashing wind to accompany the incessant rain.

Iwaya-ji, Temple 45 on the pilgrimage, is also known as the Rock Cave Temple. It is perched dramatically on a cliffside, and reaching it entails quite a climb. Finding ourselves with breath to spare when we got there, we decided to climb higher still beyond the temple. After a few minutes it was clear (to us) that there was nothing more to see, and we turned back down. A few in the group continued the steep climb up. Some people are diven by Newton's First Law: an object in motion stays in motion. We are not those people, and were momentarily conflicted, but when they rejoined us, drenched and breathless, and reported that there had been nothing up there, we felt a lot better.

We spent that night in a ryokan in the heart of the city of Matsuyama. Our bus pulled to a stop as close to the entrance as it could get, with in no time half a dozen diminutive women streamed out. Clad in tight kimonos that didn't allow much freedom of movement, and tottering on zoris with very thick wooden soles, between them they grabbed all of our suitcases and backpacks and somehow conveyed them down the alley and through the rain into the ryokan.

Dinner that evening was another kaiseki ryori. When the miso soup and rice appeared we thought the end was near, but that hope was soon dashed when they brought out the pièce de résistance. They had saved the best for last! We found ourselves staring at a fish, complete with eyes and teeth, wondering how (and why) we were supposed to to attack it with our chopsticks. One of us attempted to turn hers over to avoid the disconcerting eye contact, but a horrified waitress quickly approached to turn it back over. She explained why that was necessary, but only in Japanese, so we'll never know.

Disgusting FishThe highlight for this day was a tour of Matsuyama (Samurai) Castle, dating from 1603 and spectacularly perched above the city of Matsuyama. There were two interesting points about its lofty location. First, it offered no shelter at all from the typhoon which appeared to be ignoring the forecast that had it veering off to the east, and was instead focusing its best efforts at the very ground on which the castle stood. The second point was that a cardinal architectural rule for Samurai castles was that they be defensible. The architect of this one had achieved such impeccable defensibility that upon its completion he had to be killed, lest he design something even more defensible for a different Samurai. That was the custom. Like many castles, Matsuyama has suffered damages over the years, from lightning strikes, fire, and American forces during World War II.

Disgusting FishThe highlight for this day was a tour of Matsuyama (Samurai) Castle, dating from 1603 and spectacularly perched above the city of Matsuyama. There were two interesting points about its lofty location. First, it offered no shelter at all from the typhoon which appeared to be ignoring the forecast that had it veering off to the east, and was instead focusing its best efforts at the very ground on which the castle stood. The second point was that a cardinal architectural rule for Samurai castles was that they be defensible. The architect of this one had achieved such impeccable defensibility that upon its completion he had to be killed, lest he design something even more defensible for a different Samurai. That was the custom. Like many castles, Matsuyama has suffered damages over the years, from lightning strikes, fire, and American forces during World War II.

Matsuyama Castle courtesy M.Koberda

Matsuyama Castle courtesy M.Koberda

Our ryokan was very close to the Dogo-Onsen (communal bathhouse). The mineral springs that feed it are said to have a 3000-year-old history, but the present bathhouse was built in 1894. It is a magnificent wooden building, and although the two of us had solemnly vowed never, ever to let ourselves be talked into taking part in the time-honored Japanese custom of communal nude bathing, however unforgettable an experience that might be, we were curious to see the interior. The Emperor himself has come to bathe here, but in our defense there is a separate bath reserved for the Imperial family alone. We thought that would make a big difference.

Dogo-Onsen BathhouseThe interior of the Dogo-Onsen was a rabbit warren of corridors and staircases crowded with people who all appeared to know what they were doing. Unlike us. We were ushered into a large communal room where we were each given a wicker basket, a cotton robe and a towel, and were offered green tea and a biscuit. Our insistence that we were not going to actually get in the bath was met with incredulity, but reluctantly accepted with the proviso that we at least put some article of clothing in the basket, and the robe on our bodies, lest we scandalize bathers. That done, we were allowed to proceed to the women's changing room, which we briefly surveyed and from which we quickly fled. Apparently we missed a unique opportunity to improve our health. The water is considered healthy enough to be drunk. In the countryside, deer and monkeys come and bathe right alongside people. And if they are thirsty, the animals drink the water. It doesn't seem to hurt them, so who can argue with that?

Dogo-Onsen BathhouseThe interior of the Dogo-Onsen was a rabbit warren of corridors and staircases crowded with people who all appeared to know what they were doing. Unlike us. We were ushered into a large communal room where we were each given a wicker basket, a cotton robe and a towel, and were offered green tea and a biscuit. Our insistence that we were not going to actually get in the bath was met with incredulity, but reluctantly accepted with the proviso that we at least put some article of clothing in the basket, and the robe on our bodies, lest we scandalize bathers. That done, we were allowed to proceed to the women's changing room, which we briefly surveyed and from which we quickly fled. Apparently we missed a unique opportunity to improve our health. The water is considered healthy enough to be drunk. In the countryside, deer and monkeys come and bathe right alongside people. And if they are thirsty, the animals drink the water. It doesn't seem to hurt them, so who can argue with that?

Inside the Dogo-Onsen Bathhouse

Inside the Dogo-Onsen Bathhouse

For dinner that night we were honored with yet another kaiseki ryori. By this point we had our fill of those, but the presentation was so orchestrated and theatrical, and the waitresses so pleasant and eager to please, that we were forced to admit that the fault lay with us, not them. And we were beginning to worry more about the unrelenting rain that pounded down all night,, and what effect that might have on cancelled flights. There was a small television in an area that served as the ryokan's reception room, and without the benefit of understanding anything that was being reported, we saw dramatic helicopter rescues from raging rivers, and long rows of airplanes stranded on the tarmac of some Japanese airport.

One of Many Kaiseki Ryori Courses

One of Many Kaiseki Ryori Courses

Inevitably there dawned a day that was rain-free! We visited Temple 75, the Zentsu-ji Temple. It is the largest temple on Shikoku, and it is built on Kobo Daishi's birthplace. The thing to do at Zentsu-ji is to walk the 300-foot-long underground tunnel. It is pitch dark and curves around, so the only way to navigate it is by keeping one hand on the wall. Then, suddenly, one emerges into a small lighted room: you have passed through the darkness of life and come out into the light, enlightened. But having reached that state, one has to go back through the darkness to get out of the tunnel, which detracts somewhat from what had been rather nice symbolism.

Zentsu-jiA huge disappointment was in store for us next. We were prepared to climb the 1,368 stone steps leading to the top of Kompira-San, a Shinto shrine dedicated to sailors and seafaring. We started out energetically, stopping now and then to make sure that there was nothing in the small shops on either side of the steps that we couldn't live without. 785 steps up we reached the main shrine, winded but still determined. The rain had stopped momentarily, and we paused to take in the first good view we had had in Japan. Then, just as we were feeling confident about the remaining 583 steps to the inner shrine, the axe fell. The path to the top had been closed, due to a mudslide. We registered frustration, while silently retracting every negative thing we had said or thought about Typhoon Lan."

Kompira-san courtesy of M.Koberda

Kompira-san courtesy of M.Koberda

But Lan had still more to offer the next day; the road to Temple 84, Yashima-ji, had also been closed by a mudslide. We turned back and visited the Noguchi Osamu Garden Museum, and after the best lunch of the trip (fried chicken eaten with fingers instead of chopsticks) we walked five miles along an old pilgrim path to Temple 88, Okubo-ji, or Large Hollow Temple. It was well worth the walk. It was a beautiful temple, and featured an eternal flame that had been brought from Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

Our farewell dinner that evening was particularly festive because one of us had a birthday. Not a decade-changing birthday, but nevertheless a reason for our guide to order a magnificent chocolate birthday cake.

It is not raining now as we sit and contemplate Japan, and that makes a big difference. For one thing, it allows us to see why we ought to have enjoyed it more than we did. At the time the negatives outweighed the positives. We never really got over the 14-hour time difference, we never felt properly fed despite the long culinary ordeals, we couldn't see the scenery because of the rain, and the slippers never fit well. On the other hand the people were unfailingly courteous and helpful, and the roads, bridges and tunnels (on which we spent a lot of time) were in excellent condition. The temples were monuments to the spirituality of the people who built them as well as to the many pilgrims who visited them. Some had stunning and meticulously maintained gardens – quiet oases in which it would have been restorative to spend more time – if it hadn't been raining.