NORWAY: IT’S MORE THAN FISH AND FJORDS

Wednesday, March 4, 2015 at 12:45PM

Wednesday, March 4, 2015 at 12:45PM

After circumambulating Mont Blanc one year and crossing the Spanish Pyrenees the next, we were determined to make hiking in a different part of the world an annual thing. Since one of us had already planned to be biking in Norway the following summer, why not combine it with a hike and save on airfare? We had momentary misgivings when we discovered that few companies offer hikes in Norway. Ever cynical, we suspected the worst. Killer mosquitoes? Weird food? Non-stop rain? Still, the fabled beauty of the country outweighed our concerns, and we signed up for a hike whose description, “Mountains and Fjords (Moderate to Strenuous)”, seemed to meet our criteria.

In early August we arrived in Oslo, armed with insect repellent and warm clothes, and headed off in search of waterproof covers for our backpacks. These we had seen and coveted during a downpour on Mont Blanc, but had been unable to find in Washington. Surely Norway, boasting the highest annual rainfall in Europe, would have waterproofing down pat? We ventured into a sporting goods store, and were making headway with a sign language explanation of our needs when the salesgirl interrupted us in almost unaccented English, apologized for not having what we wanted, made a phone call to another store that did, and gave us directions on how to get there. When Ellie thanked her for being so helpful, she would have none of it: “It is my yob!”

It was an attitude we encountered everywhere we went as we spent the day visiting Oslo's attractions, and by the time we collapsed at an outdoor cafe for a restorative drink, Ellie had made up her mind to emigrate. It was a short-lived decision, lasting only until the waiter handed her the bill for her beer. Norwegians enjoy a generous network of social services (how does 10½ months of maternity leave at full salary sound?) that is based in part on their acceptance of high sales taxes across the board, but punitively high taxes on things like alcohol, tobacco and cosmetics.

We had planned to spend two days in Oslo before joining our hiking group, but while organizing our luggage on the last night there we actually read the trip notes and discovered that we weren’t to meet up with our group for another day. Luckily the fully-booked hotel was able to stash us into a tiny room, but it would not be the last time we made such a potentially dire mistake. However, out of adversity comes opportunity; two days would not have been enough to do justice to Oslo, and we made good use of every extra minute.

Our meeting point was to be in Geilo, a four-hour train ride from Oslo. We expected to eat lunch on the train, but by the time the food cart had made its way to our compartment, all sandwiches were gone. We resigned ourselves to doing without and were concentrating on the scenery when - an hour later - the attendant suddenly reappeared bearing two sandwiches she had commandeered farther along the train. Another young Norwegian, happily doing her yob!

"Living" statue in Oslo

"Living" statue in Oslo

That evening we met the eleven other members of our group and our guide, a trim, fifty-something Norwegian who had spent 30 years in the army. On first meeting he appeared taciturn, and more prepared to respond to questions than to volunteer information. It got to be a standing joke; answers to even our more complicated questions would typically consist of a long, thoughtful draw on his pipe, a studied silence, and a simple “Ja” or “No,” always uttered with a rising inflection. He clearly felt no need to drum up enthusiasm; Norway itself would take care of that. Nor was he in any way fainthearted, as we sensed when he pulled a sizeable shard of glass out of his bowl of soup, placed it calmly on the table, and announced that he wouldn’t eat that part of the meal.

The next day began with a short train ride to Finse, where we were to walk on a glacier, the Hardangerjøkulen. Before leaving we assembled our own lunches from the breakfast buffet, as is standard practice for hotel guests in Norway. The buffets typically consisted of cereals, muesli, “drinking” yogurt, herring in every conceivable form, hard and soft boiled eggs, cold meats, and various types of cow and goat cheeses. One of these was “gammelost” - literally, “old cheese.” Our guide was insistent that we give it a try; he said his grandfather had lived to a ripe old age eating little else, and never needed to see a doctor. He then watched with amusement as Suzy tried to deal diplomatically with a mouthful of something that had the texture and taste of rotting floorboards. “This,” she finally gasped, “kept him healthy?” “Ja. It had to. No doctor would go near him after he ate that.” It was the first glimpse of a deliciously dry wit that would keep us laughing for the next week.

FinseFinse (3972 feet) is the highest point on the Oslo-Bergen train line. Throngs of blond Norwegians piled out of the train there, equipped for all manner of outdoor activities. Many were hikers, and there were entire families on bicycles, the youngest nestled in “trailers” towed by a parent. From there they fanned out over the vastness of the Hardangervidda (Hardanger plateau is Europe’s largest), not to be seen again by us. On most days we had trails to ourselves.

FinseFinse (3972 feet) is the highest point on the Oslo-Bergen train line. Throngs of blond Norwegians piled out of the train there, equipped for all manner of outdoor activities. Many were hikers, and there were entire families on bicycles, the youngest nestled in “trailers” towed by a parent. From there they fanned out over the vastness of the Hardangervidda (Hardanger plateau is Europe’s largest), not to be seen again by us. On most days we had trails to ourselves.

The railroad was a feat of engineering when it opened in 1909. 2000 men had labored for ten years under the most punishing conditions to complete it. The first train to make a trial run got stuck in the snow for several days; what is now the only hotel in Finse was originally a rescue lodge. Because of its strategic location, the railroad was of great interest to both sides during World War II. The occupying Germans needed to keep it open for transportation; the British were bent on closing it down. Unfortunately, lacking "smart" bombs, the Royal Air Force repeatedly missed the railroad and succeeded only in destroying the ice-rink adjacent to the hotel - a particular loss to the skating world as it was the rink on which the young Sonia Henie used to practice.

The Hardanger Glacier is an imposing sight. It was here, in 1908-1909, that the British Captain Robert Falcon Scott and the Norwegian Roald Amundsen trained for their Antarctic expeditions. Our guide pointed out to Suzy, who is British, that Scott had actually stayed in the hotel we were in. She then did exactly what he had hoped she would do, and politely asked whether Amundsen had also stayed there. To which he was able to reply with barely concealed smugness, "No. Amundsen was an outdoor man."

It took several hours of walking over lichen-covered rocks to reach the glacier. At its foot we got our marching orders. The guide had dispensed harnesses and crampons back at the hotel, and in typical no-nonsense Norwegian style we were instructed to watch carefully as he demonstrated how they were to be put on. Taking no chances, and since our lives were going to depend on getting this right, most of us feigned complete helplessness and waited for him to do it for us. We then marched onto the edge of the glacier, and despite brilliant sunshine, we were glad of our layers of Polartec and Gore-Tex, gloves and caps. Again we were told to watch carefully, and for one bleak moment it looked as though he were going to take the same cavalier approach to roping us together that he had with the crampons. However, about this process he was very serious. We were roped in two lines, each person about twenty feet from the next, and were told not to hold the rope, but to space ourselves in such a way that it was almost taut, so that if anyone were to slip into a crevasse there would not be much slack to run out before the fall was arrested. We were to try to keep to obvious ice, avoiding snow that could be masking a crevasse. At this point we had been joined by an acquaintance of the guide, a Norwegian neurologist who had with her her Giant Schnauzer, Julia. Julia was supposed to wait for us just below the glacier while we walked on it for about an hour, but so pitifully did she protest being left behind that her owner relented and went back to get her. Once on the glacier, Julia showed remarkable prudence in deciding which crevasses to jump, and which to insist on taking the long way around, even when she was being urged across by her mistress, and they were clearly within her jumping abilities. Beyond self-preservation, Julia's other preoccupation on the glacier were the centuries-old remains of lemmings. The movement of glaciers will, eventually, cause anything caught in them to be extruded. Lemmings multiply exponentially, and every seven years their numbers trigger a hard-wired population control technique; one sets off in search of a better life, and the others follow, no matter where. Alas, lemming leaders are not always visionaries, and should the journey accidentally come to a stop at the bottom of a crevasse, an entire colony of lemmings will end up there, too.

Humans, on the other hand, have devised ways to avoid falling into crevasses, and one is to watch the person in front of you, and when they come to a crevasse, be sure they have enough rope to jump across. Everything was going smoothly until Ellie, directly ahead of Suzy, came to a biggish crevasse and was preparing to leap. Suzy moved forward to give her sufficient rope, only to discover that Julia had chosen that moment to park her ample body on the rope and play with the remains of a lemming, effectively anchoring Suzy and cutting off the supply of rope. The shortage only became apparent to Ellie when she was in the air, mid-crevasse, and realized that she might run out of rope before landing on the other side. Harsh words were uttered, but they were lost on Julia. Once safely on firm ground we asked our guide whether he had ever had anyone fall into a crevasse. “Ja,” he replied, laconically. We pressed eagerly for details: “Really? Wow! Tell us more! What happened?” He shrugged: “She didn’t yump far enough.”

The next day we took a short train ride to Myrdal, and set out on a twelve mile walk down the valley to Flåm, on the Sognefjord. A branch line of the railroad makes the same 3000 foot descent in forty minutes in what is said to be a spectacular trip, and our guide suggested that anyone whose feet were giving out could hop on the train at one of the intermediate stops. Our feet were giving out, but nothing short of collapse could have induced us to abandon the walk. Mountains rose dramatically on either side, and waterfalls tumbled down the walls of the valley. The air was crystalline, and the only sound was that of the river as it eddied and plunged over the rocks. But there is always a dark side, and in this case it was once again some goats that appeared and had no intention of leaving until properly invited to join us for lunch.  WaterfallJust before reaching Flåm we passed through the old village of the same name - a cluster of small houses amongst immaculately tended gardens and apple trees heavy with fruit. For those interested in modernity there was a small church on one side of the road, built in 1667 on the site of one dating from about 1320. For those who take a longer view of history there was a field opposite containing a number of large memorial stones erected in the late Iron Age.

WaterfallJust before reaching Flåm we passed through the old village of the same name - a cluster of small houses amongst immaculately tended gardens and apple trees heavy with fruit. For those interested in modernity there was a small church on one side of the road, built in 1667 on the site of one dating from about 1320. For those who take a longer view of history there was a field opposite containing a number of large memorial stones erected in the late Iron Age.

The next morning our tired feet were given a brief respite. We took a steamer from Flåm into the Nærøyfjord - the world's narrowest fjord.

On the grassy banks the guide pointed out Viking burial mounds. Viking activity was at its peak between the 8th and 10th centuries, and due to England’s proximity, it bore the brunt of the Vikings’ need for land and lust for treasure. Their reputation for brutality, however, pained our guide. He refused to accept that his ancestors had pillaged and raped. "No, no. Never raped. They always asked. If they were in a hurry, they sometimes had to ask afterwards, but they always asked." Often, to reinforce the truth of whatever he happened to be telling us, he would pull out the trusty knife he kept at his side and stab it meaningfully into the nearest piece of wood. We got the point.

We were to spend that night at the famous Stalheim Hotel. The first inn was built on the site in the 1650s; later it became a favorite mecca for European royalty. Kaiser Wilhelm visited twenty-five years in a row (although it was rumored that the scenery was not the only attraction that kept bringing him back). To reach the hotel we took a bus from Gudvangen, up a narrow, precipitous, hairpin-bend road. It was sufficiently terrifying when the bus had the road to itself, but when two vehicles met and one had to back up it got really interesting. Ellie, never one for heights, succeeded in petrifying the small child sitting next to her, who had been enjoying the experience until Ellie, without benefit of a common language, made her aware of the life-threatening aspects of it. However, the reward for surviving the harrowing journey was stupendous. The hotel is perched atop a cliff, overlooking a valley, and when Conde Nast went in search of the twelve best hotel room views in the world, the Stalheim Hotel made the list.

View from Stalheim HotelThat afternoon the guide proposed a challenging hike around the side of a mountain to an abandoned farm. He promised more splendid views, but warned of one or two precipitous drops. One of us, averse to precipices, opted out, settling instead for a pastoral stroll near the hotel that featured, she later boasted, some “truly amazing cows.”

View from Stalheim HotelThat afternoon the guide proposed a challenging hike around the side of a mountain to an abandoned farm. He promised more splendid views, but warned of one or two precipitous drops. One of us, averse to precipices, opted out, settling instead for a pastoral stroll near the hotel that featured, she later boasted, some “truly amazing cows.”

The other of us, for reasons of her own, felt compelled to join the small group of stalwarts trotting along behind the guide. The trail led mainly through brush and low trees, making it difficult to sense what kind of terrain it was, but at points where there was no vegetation it was apparent that on one side of the narrow trail was a steep cliff, and on the other side was a drop-off of hundreds of feet to the valley floor. Iron rods had been helpfully inserted into the rock so that children, who used to walk that way to and from school, had something to hang on to when it was icy. (Ellie wants the faint of heart, like herself, to rest assured that excursions such as that are usually optional.) The next day, from the valley floor, our guide pointed out the route that we had taken; had he done so beforehand his group would have been smaller by at least one. That night we all did justice to an extensive buffet of reindeer, shrimp, crayfish, eel and salmon.

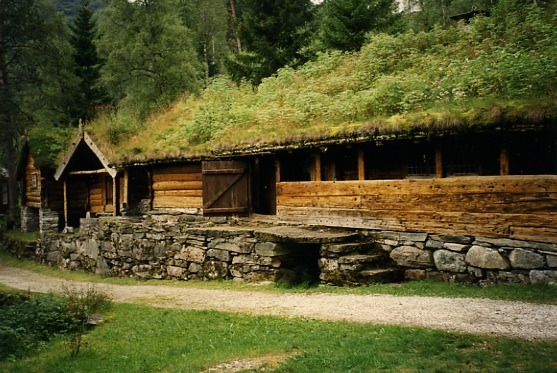

Near the hotel were several Norwegian farmhouses with their distinctive sod roofs. In addition to being cheap, these roofs were practical: all necessary ingredients were close by, layers of birch bark under the sod provided waterproofing, the sod itself was good insulation, and when the grass got dry enough to present a fire hazard, the farmer would perform cheap maintenance by simply tossing a goat up onto the roof to trim the grass.

We were eager the next day for what we were warned would be the hardest hike of all. Part of an ancient Viking track between east and west Norway, our route would take us up the Aurlandsdal - one of Norway’s most beautiful valleys - and end with the crossing of a hanging bridge.

Seeing Doubt written large on Ellie's face, our guide assured her there would be an alternative way across if she didn't like the look of the bridge - which Ellie was quite certain she would not. A short bus ride took us to Vassbygdi, at the bottom of the valley, and we began the steep, rocky ascent. It was magnificent; sheer mountains rose on either side, and a river, fed by countless waterfalls cascading down the rock walls, sparkled its way down to join the Sognefjord behind us. Along the way we passed caves in which troll women were thought to dwell; disguised as beauties, they would lure unsuspecting men into making love to them, and then drag them into the caves, never to let them go. In Norway's dangerous and inhospitable mountains, trolls usually got the blame when bad things happened, or when people disappeared without explanation. More stupid than malevolent, trolls turn to stone when the sun shines, or when church bells ring.

There were at one time six farms in the Aurland valley, but five of those families left for Minnesota during the 1860s. To be free and to own land was the ambition of every Norwegian, but in a country in which only about three percent of the land is arable, emigration was for some the only option. It often posed a dilemma, for it took the work of every generation of a family to eke out a living from the small farms.

Abandoned farm building in Aurlandsdal

Abandoned farm building in Aurlandsdal

If, as was often the case, the younger members were eager to try their luck in the New World, they either needed to persuade their older relatives to join them, or they went alone - leaving parents and grandparents to an uncertain future. This gave us something new to think and worry about: would our children or grandchildren have even wanted to drag us along with them to the New World?

About halfway up the valley we passed the point at which mothers from the farms above would meet their children coming from school far down in the valley. Above that point the path became quite treacherous. A short while later we saw just how treacherous, when we came face to face with a sheer rock wall. Luckily for us, we were attacking the wall after the discovery of TNT, and a narrow ledge had been blasted across it. The schoolchildren, however, would have had to negotiate it by means of a leather “bridge” hung from iron rods driven into the rock.

Eventually we came to the dreaded hanging bridge: two narrow boards across a chasm, through which, 120 feet below, ran a pretty active river. There were handrails on either side, and some netting which didn't quite connect with the boards. While theoretically possible to fall through the gaps, it would have required a certain determination to do so - a fact that did nothing to recommend crossing the bridge to Ellie. However, by now skirting the bridge had become academic because it entailed a much longer, circuitous route, and we all needed to be at a certain spot at a certain time in order to catch a bus to Hallingskarvet. Missing that bus was not an option. The neurologist knew her dog well enough to know that wild horses would not get Julia to cross the bridge, and she had quietly detached herself from the group some way back and set out on Option B at a pace that Ellie could never have matched in any case. Quite simply, she was stuck.

Our guide led the way, and we followed, one at a time. It occurred to Suzy that there would be good photographs from the bridge itself, so she had her camera at the ready. What had not occurred to her was the fact that the bridge would heave up and down quite a bit as one walked across, and by the time she reached the midpoint she had decided, even without looking through the viewfinder, that photographs from the bridge would not be nearly as interesting as once thought. When it was Ellie's turn to cross, the guide went back to escort her. He enjoyed this, and as they advanced he extracted IOUs from her, should she live to see the other side. Since most of his demands were in Norwegian she had no idea what she was promising - her worldly goods, her firstborn, or even her body - but on a swinging bridge 120 feet above a raging torrent they all seemed like good bargains to her. The only thing she was sure she had committed herself to was buying him a cognac that night.

The hotel at Hallingskarvet catered mainly to skiers. Adjacent to the main building were a number of small wooden cabins, immaculately clean (at least until we trudged in), and skilfully designed to accommodate the maximum number of sleepers that could be inserted into such a tiny area. There was not a wasted inch, and yet, this being Scandinavia, tucked into a closet-sized space in the bathroom was, of course, a sauna. We trekked over to the hotel for a good dinner of cauliflower soup and mountain trout, and Ellie settled her debt with the guide, which, at Norwegian prices for alcohol, was generous payment indeed.

After lunch on the final day we set out for Geilo, over terrain that was unlike any we had seen before. In winter this area is ideal cross-country skiing terrain, and tall poles, giving some idea of the customary depth of snow, mark the skiers' trails. In summer it was barren, bleak and squishy, with more of the same in all directions as far as the eye could see. Ptarmigans circled overhead, but otherwise there was no living thing. The sense of isolation was palpable.

After a final dinner in Geilo our little group began to disperse. On the train back to Oslo we rated the trip. The only negative: even for us, who look for gain with a minimum of pain, the hiking was more moderate than strenuous. On the plus side, there had been no mosquitoes, and the waterproof backpack covers that we thought would be the envy of all were still in their original wrappings. Not once had we had to deal with the infamous lutefisk - dried cod soaked in lye that even Norwegians find an acquired taste; rather, the food had been extremely good, and we felt brainier than usual as a result of all the fish. We had expected the fjords to be beautiful, and they far exceeded our expectations. But more than anything, we were charmed by the warmth, humor and character of the Norwegians, who, from our brief acquaintance, all seemed to be blond, healthy, and happy to be doing their "yobs".

click here to see a gallery of the photos