PATAGONIA: 2011

Wednesday, April 1, 2015 at 07:55AM

Wednesday, April 1, 2015 at 07:55AM So many of our friends had already been to Patagonia, and we were getting tired of fielding questions as to why we hadn't. In March we flew out of a Washington winter and into a southern hemisphere summer, to Ushuaia, the southernmost city in the world. It is situated on Tierra del Fuego, a vast archipelago separated from the American continent by the Strait of Magellan. The flight from Buenos Aires makes a dramatic approach over the mountains before landing at Ushuaia's small, modern airport on an island in the Beagle Channel. There the authorities performed an extremely thorough check for any fruits that might have been smuggled in with our luggage; after decades of benign neglect and careless introduction of non-native flora and fauna, the area is now ecologically aware and conscientious.

Suzy and Ellie in Patagonia

Suzy and Ellie in Patagonia

The Beagle Channel is named after the ship that brought Charles Darwin, the young naturalist, to the area in 1832. Anglican missionaries followed, bent on converting the native Indian tribes living in the area. The doctrine largely failed to take hold, but the diseases the newcomers introduced, and for which the Indians had no immunity, had a greater effect. No full-blooded Indians survive today.

Ushuaia itself has had a fairly successful stint as a port for the sheep and cattle farming and lumber mills in the surrounding countryside. Prisons for miscreants, both the political and the dangerous kind, were built in the city, partly as a means for promoting development of the area, and partly because sending the convicted there really did put them in a place where they could do little damage. Today the city is home to an Argentinian naval base and is heavily dependent on tourism. It is a regular port-of-call for cruise ships, and the jumping off point for Antarctica.

Ushuaia

Ushuaia

On the afternoon of our arrival we took a gentle three-hour hike through the Tierra del Fuego National Park, southwest of Ushuaia, where the southernmost peaks of the Andes disappear into the ocean. Walking through lenga and guindo forests, we saw earthen mounds that were the only remaining vestiges of the Yamanas – one of the Indian tribes that inhabited the island. They supposedly eschewed clothes (difficult to imagine at such a latitude), but were very fond of mussels. We walked along carpets of shells on a path that skirted the secluded coast and bays of the Beagle Channel.

Beagle Channel

Beagle Channel

At the end, a short detour by road brought us to the pretty Lapataia Bay and a photographic opportunity - the southern terminus of the Pan-American Highway. A small wooden sign said it all:

Aqui finaliza la Ruta Nac. No. 3

Buenos Aires 3,079 Km.

Alaska 17,848 Km.

It should be noted that the word “highway” conjures up something quite different from the narrow gravel road that actually leads to that sign, but we were assured that other stretches of it are in better condition. It depends on which country the road finds itself crossing.

Southern Terminus of the Pan American Highway

Southern Terminus of the Pan American Highway

Dinner that night was one of the best of the trip: superb fresh fish and crab legs served up by a French chef in a restaurant on a hillside overlooking Ushuaia.

The next day began with a long drive over stone roads. (Caveat to the unwary: Patagonia is full of long drives for all but the most hardy campers. If you require beds and toilets, be prepared to spend hours on roads getting to them.) The day was again warm and sunny, and we were told that two such flawless days in a row were quite rare. Using a combination of van, Zodiac boats and our own feet, we explored islands in the Beagle Channel, walking as quietly as we could through tall stands of trees where the only sounds were those of birds calling, and the imposing Magellanic woodpeckers hard at work. By midday we had reached an old sheepshearing station, so long abandoned that it had been overgrown with grasses and bushes. But behind it was the small shelter for the shearers, and our van driver had miraculously made his way to this from the parked van, hauling everything necessary for an enormous lunch of sausage, steak, salad, and cheese, with abundant wine. (We've not yet mentioned that Argentinian wine is good, plentiful, and in some cases cheaper than water - particularly water bought in a small convenience store near a hotel in downtown Buenos Aires where the shopkeeper immediately pegged us as American tourists who hadn't yet figured out the exchange rate.) Recharged, we staggered back to the waiting zodiac to be whisked over to a penguin reserve on Martillo Island.

Penguin Colony on Martillo Island

Penguin Colony on Martillo Island

Penguins we had seen before, but never in such abundance. As far as the eye could see, thousands of Magellanic and Gentoo penguins stood like sentinels, unconcerned by the intrusion. Visitors are permitted to spend no more than twenty minutes on the island, and are cautioned to make no loud noises or sudden movements. The penguins had nothing to fear from us, but they did need to be mindful of the ugly skua birds in their midst, patiently awaiting the opportunity to snatch a penguin egg.

We left Tierra del Fuego reluctantly, and with the feeling that we had barely scratched the surface of that extraordinary part of the world. No doubt the weather contributed; under different conditions that flight out might have come not a moment too soon. Ours was a one-and-a-half hour flight to El Calafate, one of only a few cities in Argentinian Patagonia, and the nearest airport to a number of popular destinations. From there we were to drive four hours on a good road over barren steppes, to El Chaltén.

Approach to El Chaltén

Approach to El Chaltén

We saw perhaps two other cars on the way, but there was great excitement when we saw our first guanaco. We leapt out of the bus, cameras at the ready, to record the unique occasion. (Ten days later we had seen so many hundreds of them that we barely turned to look in their direction.) We also saw our first Andean condors, and they never failed to impress. Their sheer size and gracefulness as they rode the air currents in that vast landscape made for an unforgettable sight every time.

There is one cafe/lodge/roadhouse/gas station between El Calafate and El Chaltén. Just the one. La Leona is not only a modern-day mecca for anyone traveling that road, but was also a “technical stop” for three “gringos” who spent more than a month there in 1905, and who were later identified to the police by the proprietor as none other than Butch Cassidy, Sundance Kid, and his wife, Ethel Place. They had just robbed a bank and were making their way to Chile. Our stop there was shorter; long enough for a early supper of empanadas before continuing on the long drive to El Chaltén.

La Leona

La Leona

That part of the drive had been timed to perfection. The sun was beginning to set just as the Fitzroy Massif (which is to El Chaltén what the Matterhorn is to Zermatt) came into sight, its perpendicular walls bathed first in sunlight and then in pink before disappearing into the darkening sky. We couldn't wait to get to it!

El Chaltén itself disappoints. Begun only in 1996, it has the feel of a purpose-built hub for trekkers, climbers, and other sports enthusiasts, but charm has been overlooked. Our hosteria was a further half-hour drive beyond the town, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, but actually well located for the next day's hike. It was late and dark by the time we reached it.

As was to be the pattern, we each assembled our own lunch from a simple buffet that was spread out in the dining room the next morning. Outside the rain was pouring down, and the wind (a constant feature in Patagonia) was whipping around as we set out over rolling hills on a 1000 foot ascent to the base camp for mountaineers attempting to climb Fitzroy. Beyond that was a bridge to be crossed - two narrow boards over an active little river - which was made quite interesting by the 50-60 mph winds that were now actually knocking some of us off our feet.

Wind

Wind

We had to crouch down and wait for a temporary lull before attempting the single-file crossing. Further along we came to a shelter where we could contemplate the remaining one mile, 1200 foot ascent, consisting mainly of the kind of high steps that are so punishing to aging knees and thighs. Our guide declared it “dangerous” in such conditions, and appeared to be looking directly at the two of us as he said it. Letting discretion be the better part of valor, we parked outselves in the shelter, addressed our packed lunches, and then made our way back to El Chaltén, where one of us quickly spotted a microbrewery that needed a customer. When the rest of our group rejoined us they insisted that they had had a fabulous climb, but that some of them had indeed be blown over by the wind. The chef at our small hosteria proved that night that his skills were not those of a backwater cook; he produced a delicious loin of lamb and equally good accompaniments.

If anything, the weather deteriorated overnight. Our hike the next day, to a glacial lake, was highlighted by cold, rain, hail and wind. We struggled up to the lake, looked at it obediently for a few seconds, then quickly retreated off the ridge to a slightly more sheltered clearing in the forest where we ate our now soggy lunches.

Some of us washed them down with cups of yerba maté. This was something our guide was never without. A bag of the dried maté leaves and a thermos of hot water were always close to hand, and during the long bus rides we had watched the cup and straw being passed between guide and driver. We had picked up some of the unspoken rules of the ritual: one simply adds more hot water to the cup as necessary, but on no account is the drink to be stirred, and it is not polite to thank the person who hands it to you, unless you mean to indicate that you don't wish to drink any more (something we never witnessed happening). Furthermore, the fact that the traditional maté cup has a pointed base that makes it impossible to set down on any surface doesn't appear to present a problem as the drinkers never want to set it down anyway. Observing this interaction over many hours and miles had whetted our curiosity as to what makes maté so seemingly addictive and appealing. Now that we have tried it ourselves, we are still wondering.

After two days in and around El Chaltén we climbed back into the bus for the long drive to Estancia Helsingfors. Most of it was on a gravel road across the generally deserted steppe, the monotony punctuated only by guanacos, flamingoes, and Andean condors. But eventually we turned back into the mountains and arrived at the estancia. The beauty of the estancia and its isolated setting on Lago Viedma had been highly touted; it had not been exaggerated. It was founded by an immigrant Finn in 1902 as a sheep ranch, and now accommodates a small number of visitors during the summer season. An outdoor barbecue awaited us near the shore of the lake, with what looked like an entire sheep, sausages, potatoes and salads. Plenty of Malbec contributed to the feeling of well-being.

Lago Viedma

Lago Viedma

On offer for the afternoon was a hike to a peninsula which would afford an overview of the Viedma Glacier. But also on offer were the usual Patagonian winds, now reaching 70-80 miles per hour, along with a steep, gravelly path. Not everyone opted for the peninsula, and those who did pronounced it hard going, albeit with a grand view of the Fitzroy Massif when the clouds obligingly parted. And even those of us who had done nothing to work up an appetite enjoyed a wonderful dinner: pisco sours and hors d'oeuvres by a fireplace, followed by pumpkin soup, trout and a tarte Tatin.

The next day there was a horse option. In the interest of full disclosure, one of us had “blown out” her knee in El Chaltén and was having a little trouble with the downhills. And since downhills are a significant and unavoidable part of hiking, Suzy was more than happy to clamber up on Diamonte and let his knees do the hard work. At the point where the horses could go no further there was a walk up over a ridge to the accurately named Lago Azul. Most, including Ellie, then set out on foot for the long walk back to the estancia. Suzy and Diamonte set out on hoof.

Lago Azul

Lago Azul

From Helsingfors we turned back to El Calafate, which was to be our jumping off point for the Perito Moreno Glacier the next day. The glacier is a popular tourist destination. It is not only hugely impressive – three miles wide at its face and almost 200 feet high - but also easily accessible by bus and boat for those who simply want to look at it, and safely walked upon by those with a bit more pluck. It is one of the few glaciers in the world that is still advancing. We were among the plucky ones, and after a short boat ride across Lago Argentino we walked by the side of the glacier to the point at which we were to put on crampons and begin the walk on the glacier. We had both walked on glaciers before, but this was in a different category altogether. We were given our Crampon 101 lecture, the essentials of which were to stab one's foot into the ice as forcefully as possible, and to approach both uphills and downhills straight on, leaning forwards or backwards respectively. This is counter-intuitive because faced with a steep slope, be it up or down, every braincell one has is urging a side-step approach and a sideways into-the-hill lean, the better to break the inevitable fall. And that is definitely the go-to position when disaster looms, as we both found out. But the guides knew whereof they spoke; the ice was not smooth like ice cubes, but granular, so that when one stamped one's crampons in, they stayed firmly stamped.

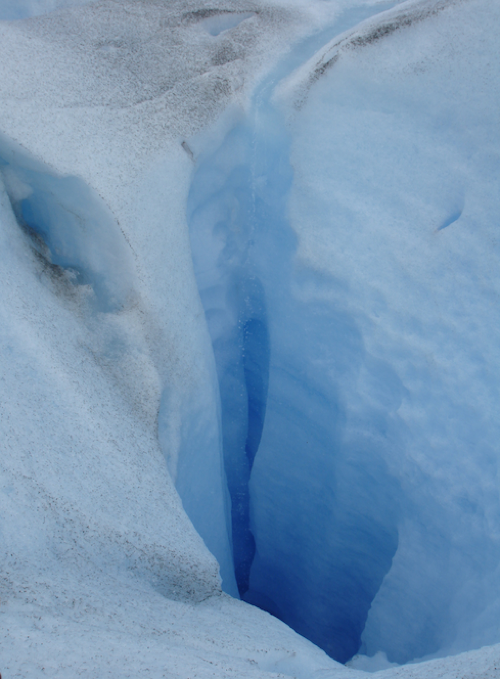

The best way to describe being on the glacier is to liken it to tramping around on a gigantic lemon meringue pie. It's as if someone had beaten the egg whites until they held stiff peaks, swirled them around with a spatula, and then dropped some cobalt blue or turquoise food coloring into the resulting crevasses. These yawned on either side, with no visible bottoms, but our guides assured us that if we fell down one we would only get wet, not killed. And in the final analysis it was all too breathtakingly beautiful to allow time for fear.

Blue crevasse

Blue crevasse

Back on the other side of Lago Argentino a series of catwalks had been constructed, from which one could ponder the enormity of the glacier, and watch the frequent “calving” that occurs when enormous chunks of ice break loose, thunder down into the water, and then float serenely over the surface of the lake as icebergs.

Glacier calving

Glacier calving

So much for Argentinian Patagonia. The following day we were to cross the border and make our way into Chile. We stopped for lunch before the border at a sheep estancia – the only habitation between El Calafate and the Chilean border, and as a result something of a tourist stop. There we were treated to a display of a sheepdog going through the paces, and could only think how much the sheep must have hated the sight of a bus disgorging tourists, knowing full well what was going to be next on their agenda. There were rheas to admire, but only from our side of the fence; they are strong and they bite and scratch. And the owner of the estancia gave us a demonstration of sheepshearing, removing all the wool from one animal in one piece in a deft 15 minutes. We were impressed until we heard that the itinerant shearers who make the rounds of the estancias during the shearing season get the job done in about two minutes per animal.

Sheep shearing

Sheep shearing

The border between Argentina and Chile consisted of two unprepossessing buildings down a gravel road in the middle of nowhere. We piled out of the bus at the first in order to leave Argentina, and again at the second a few minutes later in order to enter Chile. All our luggage had to be x-rayed by the Chileans. Between the two buildings is a no-man's land, controlled by police and not to be photographed, which seemed incongruous, given the bleakness and remoteness of the terrain. Then again, Argentina and Chile have not always been the best of friends.

Our destination, quite a bit later in the day, was a small hotel just outside the boundary of Torres del Paine National Park, where we were to spend the next three nights. Now we were to get our first view of the fabled granite towers of the Paine Massif.

First view of Paine Massif

First view of Paine Massif

They do not disappoint. They are high, sheer, and dramatic beyond what photographs can portray, and on this particular day the setting sun cooperated magnificently. The park itself was created in 1959 and declared part of the Biosphere Reserve Network by UNESCO in 1978. It is a hiker's paradise, and a mountaineer's challenge; the face of one of the towers is a vertical 4,000 foot of rock.

We were content with a more horizontal walk the next day to a lookout point from which one could see vast areas of the park, studded with braided rivers and blue lakes. Chile recognized the potential tourism value of its part of Patagonia long before Argentina, and some of the hotels in the park are huge, with varying degrees of charm. However, gazing out over the expanse of the park from the top of that hill gave a feeling of a world without people, or any trappings of modernity.

Braided river

Braided river

The descent from the lookout point was more difficult for the one of us with the complaining knee; it was long, steep, and over scree. Our bus awaited us at the bottom, and took us to one of those aforementioned large hotels, where the number of guests overwhelmed the waiters in the dining room, and a dinner of lamb and congor took far longer than we would have liked.

Descent from Mirador Toro

Descent from Mirador Toro

The highpoint of the next day was a hike to a windblown bench. The attraction of this particular bench was its situation on a promontory overlooking a lake, directly beyond which rose the Torres in all their dramatic splendor. That view was indeed worth the struggle to get to it, but a struggle it was. The wind was gusting at between 70 -75 mph, and that kind of ferocity is enough to knock one off one's feet. We quickly learned to hunker down as low to the ground as possible whenever we heard a gust gathering up some steam and coming our way. The bench, when we finally reached it, was anchored into concrete, but only large enough for a few of us to sit on; the others had to crouch behind it, as low to the ground as possible if they didn't want to to become airborne. Trying to stand was just foolhardy. It had taken an hour and a half of hiking to reach this point, so there was some pressure to stay and admire the view once we got there. There were the Torres, smack in front of us. Below them we could see the wind whipping across the surface of the lake towards us, kicking up plumes of spray, and we could predict precisely when the next “glacial facial” was going to hit us. It was nature's own answer to a skin peel.

The Hosteria Las Torres, where we were to sleep the next two nights, has a convenient location in the sense that one can walk right out the door and onto a number trails, but an inconvenient one in the sense that it is accessible only by way of a very narrow bridge – too narrow for the buses that have brought people to within sight of the hotel, but not quite within walking distance of it, and very definitely on the wrong side of the bridge. All luggage has to be unloaded, and passengers have to wait for the hotel to dispatch one of the small vans that are able to navigate the bridge with – no exaggeration – about one inch clearance on either side. Even drivers who do this day in and day out take it very cautiously.

That evening we were given an outline of the next day's two options. The full hike was the pièce de résistance of Chilean Patagonia, a 14 mile, eight hour day, climbing through forest and scrambling over boulders and scree, up the Valle Ascencio to the very base of the Torres del Paine. It sounded spectacular, but the fly in the ointment was that, once embarked upon, there could be no turning back. It was not without its dangers, and the guides needed to have everyone within their sights at all times. Those with any misgivings would have to turn around at the little rifugio about a gentle third of the way up. What can we say? The weather wasn't good, and it looked like there might be no view at all – after all that work! There were others who were opting for the early turn-around, and reluctantly we decided to join them. We did rationalize that doing so was an act of altruism on our part, as we might have turned what was billed as an eight hour day into a ten hour one, or even longer, for our friends. That's our story, and we're sticking with it.

Valle Ascencio

Valle Ascencio

Back at the hotel we wrestled with a moral dilemma: did we hope that the questionable weather would turn even worse, obscure all views, and justify our not having made the attempt, or did we wish the best for our fellow hikers? We killed the time learning new card games with others who had shown themselves to be faint of heart, and many hours later the summiters strolled back in, looking triumphant, outdoorsy, and smug. Everything we had thought we were until we had come on this trip. As if by magic the clouds had parted just as they arrived at the base of the towers, and there they were - magnificently arrayed in front of them. They tried to play the scene down, out of kindness to us, but we saw right through that.

Torres Del Paine

Torres Del Paine

Was that an anticlimactic end to our Patagonian adventure? Only if we allowed ourselves to think so. It's yet one more benefit we've gotten from this kind of travel; we've learned to gracefully accept that there are things we cannot now do (and probably never could), but to take great pride and pleasure in accomplishing those that we can do. It may well go under the heading of maturity.

click here to see a gallery of the photos