DOLOMITES, ITALY: 201

Sunday, May 24, 2015 at 06:49PM

Sunday, May 24, 2015 at 06:49PM We had both fallen in love with the Dolomites many decades earlier when we had skied there together with our young children. How could one not? The mountains are jagged and dramatic, the valleys lush. The food is a happy combination of Italian and Austrian, with pasta, wurst, funghi, tiramisu and Kaiserschmarren, all delicious, and all on offer at the huts that dot the lower elevations. And the area's rich and sometimes turbulent history has resulted in a sometimes baffling linguistic potpouri from one valley to the next. Brushing up on your Italian before setting out will stand you in good stead in some places, but in others you'll do better in German. In some valleys the mother tongue is Ladin (also known as Ladino, Ladein or Romantsch) an ancient language that is still spoken in parts of eastern Switzerland.

We had always intended to revisit the Dolomites, and when we came across a twelve-day hike billed as “Moderate to Strenuous,” it seemed like something we should do sooner rather than later. “Strenuous” was beginning to assume ominous connotations. It was a wise decision. Skiing in those mountains is in many ways easier than hiking. Provided they have mastered the basic skills of turning and stopping, skiers generally let technology help move them upwards and gravity move them downwards. The hardy hiker has only his lungs and legs to get him from here to there, and there are many miles and lots of feet of elevation and descent between here and there.

We gave ourselves a couple of days in Venice before the hike and on the appointed day we took a water taxi directly from our hotel on the island to the airport on the mainland. There we met our group - fourteen hikers and three guides – and boarded the two vans that would take us north into the mountains, and be our support vehicles for the duration.

Our first stop was Bassano, a small city situated on the route between Austria and Italy. Due to its strategic location it has often been the scene of battles, most recently between the Nazis and partisans. Bullet holes in the buildings along the river remain as grim reminders. A short distance out of town we were treated to the first of a succession of sumptuous meals. It was a country restaurant, busily preparing for a wedding that was to take place later that day, but even we who were not decked out in wedding finery were fed royally on salads, risotto with pears, melon and squash, and a salted cod dish (bacalo) in honor of the Salted Cod Festival currently being celebrated – salted cod being a staple of the region.

Bossano

Bossano

The full name of the city is Bassano del Grappa, and it was there that grappa made its first appearance almost 1000 years ago. There was, of course, a grappa museum for us to visit. A film explained the process involved in producing the highly potent aperitif, and a little shop had dozens of different varieties for sale in elegant thin-necked bottles. We would have been tempted to get some early Christmas shopping done had the bottles not looked so fragile, and had we not actually tried drinking some of it. Suffice to say it is best drunk in very small quantities.

We were driven on, one hairpin bend after the other, to our hotel in beautiful San Martino di Castrozza, a ski resort in winter and a hiker's paradise in summer. After a multi-course dinner we got our briefing for the next day. We would be passing through three villages, each with a different language and different culture: Italian, German, and Ladin. And the hiking would be hard.

It was. We began by walking virtually straight up, some 2000 feet, and during the course of the day we chalked up two summits: Tognazza (7300 feet) and Grande Cavallazza (7700 feet), inspected some of the remaining World War One bunkers in this hotly contested part of Europe, and stopped for the regional specialty of polenta at lunchtime.

The briefing that evening was even more daunting than the one before. We would be encountering segments of the via ferrata, literally “iron way” - a series of ladders, iron chains and handholds that had been installed to enable soldiers to make their way in the mountains during the First World War. One of us had always thought the via ferrata would be fun to try; the other viewed it more realistically as something to avoid at all costs. On this particular hike it had been promised that there would always be an alternative route for the faint-hearted, leaving only one of us undecided. During the course of the briefing, phrases like “certain death” and “you are gone” crept in, and feigned bravery was ebbing rapidly. But as luck would have it a steady downpour the next morning ruled out the via ferrata for the entire group. For that day, anyway; it would reappear a few days later.  Via FerrataInstead, some of us went to Bolzano to visit a man who had met certain death in the mountains, but not while trying to navigate the via ferrata. Ötzi, as he has been named because of his discovery in the Ötztal Alps, died some 5000 years ago, but his remains were only discovered in 1991, quite accidentally, by a couple hiking at an altitude of 10,500 feet. A combination of fortuitous circumstances had resulted in his body, fragments of his clothing, and some of his tools being preserved in good enough condition that archaeologists have been able to learn much about neolithic culture from them. Both Italy and Austria were eager to claim Ötzi as a native son. According to the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) the border between Austria and Italy in that remote area was to run along the watershed, but the many glaciers made it almost impossible to determine precisely where the watershed was. In the end agreement was reached: Italy would keep Ötzi, but all research concerning him would be conducted by the University of Innsbrück in Austria. The South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano now has a permanent Ötzi exhibition, and it was well worth joining the very long line to get in.

Via FerrataInstead, some of us went to Bolzano to visit a man who had met certain death in the mountains, but not while trying to navigate the via ferrata. Ötzi, as he has been named because of his discovery in the Ötztal Alps, died some 5000 years ago, but his remains were only discovered in 1991, quite accidentally, by a couple hiking at an altitude of 10,500 feet. A combination of fortuitous circumstances had resulted in his body, fragments of his clothing, and some of his tools being preserved in good enough condition that archaeologists have been able to learn much about neolithic culture from them. Both Italy and Austria were eager to claim Ötzi as a native son. According to the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) the border between Austria and Italy in that remote area was to run along the watershed, but the many glaciers made it almost impossible to determine precisely where the watershed was. In the end agreement was reached: Italy would keep Ötzi, but all research concerning him would be conducted by the University of Innsbrück in Austria. The South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano now has a permanent Ötzi exhibition, and it was well worth joining the very long line to get in.

Better weather the next day had us taking a chairlift up towards the Forcella dei Camosci, a high mountain gorge. We zigzagged through an enormous boulder field before coming to the dramatic Torre di Pisa – a rock whose tilt gives it an unmistakable resemblance to its namesake in Pisa. It was high and exposed, and after lunch we were happy to start making our way down. It was steep scree, so the sense of well-being lasted only a few minutes before the knees began to protest.

Dinner that night was an occasion. A chef who had worked at a very trendy restaurant in Denmark had opened his own place nearby. It was still in the start-up phase - the chef's mother was washing the dishes and his father was doing something useful about the place - but he knew good food, and emerged from the kitchen, beaming, to receive our lavish compliments after each course. By the time we came to writing anything down later that evening we could only remember twelve of the courses, along with the fact that when our guide suggested some grappa as the perfect way to end the meal, most of us conceded defeat.

Via Ferrata

Via Ferrata

Our next night was to be spent in the Rifugio Alpe di Tires, and to get there required climbing 3000 feet with no switchbacks or flats. Parts of it were what we called via ferrata light: steps had been cantilevered out from the steep rock face and steel cables had been installed. It would have meant certain death if one fell, but it would have taken a serious lack of concentration to do so. The rifugio was dramatically situated just below a very exposed saddle, the Tierser Alpjoch Pass (8,000 feet), and has been offering food and shelter to climbers for more than half a century. We were beyond shattered by the time we reached it, but it was more than comfortable and the apple strudel was more than good. Moreover it had electricity all night, and card playing was allowed! It was one of those hate-to-leave places.

Refugio Alpe di Tires

Refugio Alpe di Tires

Our long descent the next day took us over one of the most expansive meadowlands in Europe – the beautiful Val Gardena. Our destination was Urtijëi, or St. Ulrich in Gröden, or Ortisei, depending on the language being used. For the local population it would be the first of those, for we were now in a largely Ladin-speaking part of the Dolomites. Ladin has a complicated history, but is generally thought to have developed around 15 BC, when Roman troops were sent to subdue indigenous Celtic resisters. Some ended up staying – and very eager to be able to relate to the local inhabitants! The spoken language is unintelligible, but with some command of Latin, German and Italian, it is possible to decipher certain written words. One won't of course need to; they all speak English.

Val Gardena

Val Gardena

Out of St. Ulrich (the more commonly used name) our old nemesis, the via ferrata, came back to haunt us. The beautiful weather was no longer providing any alibis, and just when we thought ourselves trapped, we were given a miraculous reprieve in the form of toe bang. It was on Ellie's foot, so she got the considerable discomfort, while Suzy got the get-out-of-the-via-ferrata-free card. Solidarity and friendship would never have allowed her to let Ellie travel in the van by herself. Moreover, toe bang does not heal overnight. A remedy was sought from a pharmacy in the village, but as far as we could make out from the accompanying instructions, it called for soaking one's foot in a “glass” of water. Ellie had not the glass, the patience, nor the right sized foot. We could say that Suzy was bitterly disappointed by this turn of events, but it would not be true.

What would be true to say is that from that point forward we began to focus more on each day's food: foccaccia, crepes, John Dory fish, venison ragout, zabaglione, very old and delicious cheeses, and pasta in shapes and sauces that bore no resemblance to what passes for pasta at home. Being invalided out of hiking in the Dolomites is no great hardship. And when our group returned from the via ferrata (intact) we listened indulgently to their accounts of fear (most of them) and nonchalance (a few of them).

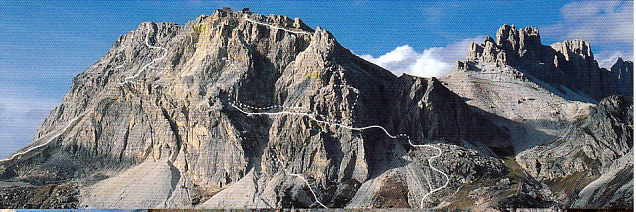

The high point of the trip was still ahead of us – the magnificently situated Rifugio Lagazuoi (9,030 feet), where we were to spend the night. The rifugio is accessible by cable car from Passo Falzarego, and sits atop an extensive tunnel system constructed during World War I, inside the massive rock tower of Lagazuoi. It was the scene of intense fighting between the former enemies, Austria and Italy, and it is possible to view a small part of the tunnel system only a few steps from the rifugio. Those with energy and no sense of claustrophobia can still cover the entire 2000 feet of it, either upwards or downwards, inside the mountain. It's hard going in either direction, but the via ferrata inside the tunnels helps. So we were told; toe bang was still preventing us from doing things we would otherwise have relished.

Lagazuoi

Lagazuoi

We did relish the rifugio. We had a small room with a balcony that opened onto the top of the world. From the terrace below we could watch all manner of alpine birds swirling and settling on nearby rocks and pinnacles. It was perhaps the most unforgettable scenery of a trip already packed with it.

The final two nights of the trip were spent in Cortina d'Ampezzo, commonly referred to simply as Cortina. The town was under the Austrian monarchy until 1918, and only became part of Italy in 1923. It was to have hosted the 1944 Winter Olympic Games, but those were cancelled due to World War II and Cortina finally got its moment of Olympic fame in 1956. Since then it has blossomed into a chic mecca for winter sports enthusiasts from around the world, and grown from a tiny hamlet into a town large enough to warrant a pedestrian zone and plenty of high-end shops.

High-end shops were not on our agenda, however. We had one last hike planned, and an hour-long drive brought us to a very high, desolate and lunar-like regional park. Amid scree and jagged pinnacles our route took us around a wide, open bowl overlooked by the majestic Tre Cime di Lavaredo, one of the most distinctive and photographed mountain groups in the Alps. The weather was perfect for hiking, neither too hot nor too cold, but emerging from the rifugio an hour later, pleasantly stuffed with more garlic than most people eat in a lifetime, we were startled to find ourselves in heavy rain mixed with hail, zero visibility, and getting colder by the minute. Even with fleece, Goretex and mittens it was a miserable descent.

The rain continued for the remainder of the day and evening, and might have dampened (no pun intended) our memories of the entire trip had not the rest of it been so utterly enjoyable. We awoke the next morning to see snow on the mountains around Cortina. And within hours we were back down near sea level, warm, and stuck in a traffic jam in Mestre. Quite enough culture shock for one day.