Kilimanjaro (1999)

Why climb Kilimanjaro? A good question, to which, being still only in our sixties, we had a ready answer: Why not? As a mountain, Kilimanjaro can’t compete with Everest, and yet it does have things going for it, including major bragging rights.

Ellie and Suzy at Uhuru PeakOn the list of the highest mountain on each of the seven continents, Kilimanjaro comes in a respectable fourth - behind Everest by a long shot but able to hold up its head alongside Aconcagua, South America’s highest peak at 22,834 feet, and Mount McKinley, North America’s highest at 20,320 feet. Kilimanjaro, Africa’s entry, is close behind at 19,340 ft. Another advantage: unlike its competitors, Kilimanjaro is considered a non-technical climb - essentially a walk in the park, albeit a park that has had most of the oxygen sucked out of it. And thirdly, sitting just a couple of hundred miles south of the Equator, it is not impossibly cold, even at the summit. Miserably cold, yes, but not impossibly cold. Indeed, when the first European ever to set eyes on Kilimanjaro reported to the Royal Geographical Society in London that he had seen a snow-covered mountain almost on the African Equator, he met with open ridicule from the members of that illustrious body.

Ellie and Suzy at Uhuru PeakOn the list of the highest mountain on each of the seven continents, Kilimanjaro comes in a respectable fourth - behind Everest by a long shot but able to hold up its head alongside Aconcagua, South America’s highest peak at 22,834 feet, and Mount McKinley, North America’s highest at 20,320 feet. Kilimanjaro, Africa’s entry, is close behind at 19,340 ft. Another advantage: unlike its competitors, Kilimanjaro is considered a non-technical climb - essentially a walk in the park, albeit a park that has had most of the oxygen sucked out of it. And thirdly, sitting just a couple of hundred miles south of the Equator, it is not impossibly cold, even at the summit. Miserably cold, yes, but not impossibly cold. Indeed, when the first European ever to set eyes on Kilimanjaro reported to the Royal Geographical Society in London that he had seen a snow-covered mountain almost on the African Equator, he met with open ridicule from the members of that illustrious body.

Once we’d made our decision, we began making preparations. One of us trained as she usually did – climbing the stairs in her house with several volumes of Yellow Pages in her backpack. The other spent vast sums of money on a professional trainer. Result? Once again, doing your walking in and with the Yellow Pages is the better way to go.

On arrival at Kilimanjaro International Airport (far less grand a terminal than its name suggests) the immigration authorities scrutinized our documents intently, wielding their rubber stamps tirelessly on any piece of paper that contained unused white space. Those formalities completed, twelve of us assembled ourselves around the man who was to lead us up the mountain. He was a member of the Chagga tribe, born on the slopes of Kilimanjaro, and was to prove a careful and conscientious guide with a fine sense of humor. Our ages ranged from 63 down to 16 with the two of us claiming the top spots by a wide margin.

We spent two nights in Arusha recovering from jet lag. In the middle of what seemed like nowhere, at the end of a dirt road, behind a manned gate, was a wonderful little Swiss-run oasis. On the lawn was a barbecue pit with several men furiously barbecuing all kinds of meats, including ostrich and zebra, along with the more mundane chicken and pork. Waiters circulated among the tables and sliced the meat off the large skewers onto our plates. That night we slept behind mosquito netting and under puffy duvets, and in total darkness. The Swiss are nothing if not thrifty, and the generator snapped off whenever it wasn’t absolutely necessary.

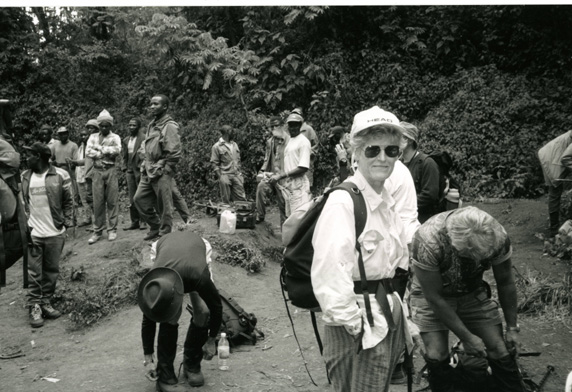

Trailhead at the start of the Kilimanjaro climb, with EllieThe next morning our guides briefed us for the climb. Our route up the mountain would be the Shira Plateau route - seven days up and two days down. It’s the longest of the regularly traveled routes to the summit, but also the one with the highest success rate. The greatest obstacle between us and the summit, we were warned, would be altitude sickness, and that was not to be taken lightly. Kilimanjaro exacts its tribute in a number of deaths each year, and prominent signs at all park entrances warn of the dangers. The best preventative, besides a slow ascent, is to drink copiously - anywhere from three to five quarts a day, whether you feel like it or not. These were to be our watchwords on the climb: “Pole, pole!” (Swahili for “slowly, slowly”), and “Drink, drink!” A few disclaimers were added, such as the fact that there are no helicopters available in Tanzania, should an emergency evacuation be needed, and our guide heartily recommended that we try not to need one. (Typical of us to have spent good money buying insurance for just that purpose.)

Trailhead at the start of the Kilimanjaro climb, with EllieThe next morning our guides briefed us for the climb. Our route up the mountain would be the Shira Plateau route - seven days up and two days down. It’s the longest of the regularly traveled routes to the summit, but also the one with the highest success rate. The greatest obstacle between us and the summit, we were warned, would be altitude sickness, and that was not to be taken lightly. Kilimanjaro exacts its tribute in a number of deaths each year, and prominent signs at all park entrances warn of the dangers. The best preventative, besides a slow ascent, is to drink copiously - anywhere from three to five quarts a day, whether you feel like it or not. These were to be our watchwords on the climb: “Pole, pole!” (Swahili for “slowly, slowly”), and “Drink, drink!” A few disclaimers were added, such as the fact that there are no helicopters available in Tanzania, should an emergency evacuation be needed, and our guide heartily recommended that we try not to need one. (Typical of us to have spent good money buying insurance for just that purpose.)

Before setting out we had to have our duffels inspected, contents checked off, superfluous items jettisoned, reinspected, and then we each had to watch our own duffel be loaded into the van. There are no second chances on Kilimanjaro. At the park entrance we met the thirty-eight assistant guides, cooks and porters who would help the twelve of us get up the mountain. They were a cheerful bunch of men, with ready smiles and "Jambo’s" (Swahili for “Hello!”). The porters stuffed our large duffel bags into sacks, leaving us to carry only our backpacks and liters and liters of bottled water. We set out at what seemed like a pretty good pace through dense montane forest, and in almost no time got our first reality check: the porters, who had stayed behind to organize things, now streaked past us, carrying anywhere up to 60 lbs. on their heads and shoulders. This would be the daily pattern; outfitted in good boots, Goretex, and other state-of-the-art hiking gear, we would haul ourselves out of our tents, wrap ourselves around the breakfast that was set up in the mess tent, and then hit the trail. The porters would wait until we had left, clean up after us, break camp, and load onto their heads and shoulders everything that was needed to supply fifty-some people for nine days. Then, wearing ill-fitting shoes or sometimes even barefoot, they would overtake us on the trail before we had got our second wind.

SuppliesThe first night we camped in the forest at 9,000 ft. Our tents had been set up by the time we got there, and we dumped our backpacks inside ours and marched off to the mess tent for dinner. The tent doubled as a dormitory for some of the porters at night; they would have what sounded like a riotous time, often playing cards, before bedding down for the night on what had a few hours earlier served as our rickety dining room table. After dinner we sat happily around a campfire until bedtime. Never once did we anticipate the difficulties of two utterly inexperienced campers trying to set up housekeeping and sort out the mysteries of sleeping bags in a cramped, and now dark and very chilly tent. We had our own liners inside the sleeping bags that had been provided, and if one twisted around during the night, the liners twisted in the opposite direction, trying to choke you to death. Furthermore, our tent that night was pitched on a slight angle so that the sleeping bags kept trying to slither out onto what we fondly called our “patio” - a muddy piece of white canvas that covered the ground just outside the tent flap. Add to all the above the novel experience of the latrine, and its attendant toilet-paper-kerosene-and-shovel ceremony, and we were feeling a bit challenged by the time we crawled into our mummy sacks.

SuppliesThe first night we camped in the forest at 9,000 ft. Our tents had been set up by the time we got there, and we dumped our backpacks inside ours and marched off to the mess tent for dinner. The tent doubled as a dormitory for some of the porters at night; they would have what sounded like a riotous time, often playing cards, before bedding down for the night on what had a few hours earlier served as our rickety dining room table. After dinner we sat happily around a campfire until bedtime. Never once did we anticipate the difficulties of two utterly inexperienced campers trying to set up housekeeping and sort out the mysteries of sleeping bags in a cramped, and now dark and very chilly tent. We had our own liners inside the sleeping bags that had been provided, and if one twisted around during the night, the liners twisted in the opposite direction, trying to choke you to death. Furthermore, our tent that night was pitched on a slight angle so that the sleeping bags kept trying to slither out onto what we fondly called our “patio” - a muddy piece of white canvas that covered the ground just outside the tent flap. Add to all the above the novel experience of the latrine, and its attendant toilet-paper-kerosene-and-shovel ceremony, and we were feeling a bit challenged by the time we crawled into our mummy sacks.

RestroomWe were feeling even more challenged by the time we crawled out of them the next morning, because neither of us had slept well, due to the cold. If this was a problem at 9,000 ft., we dreaded to think how we would do at 19,000 feet, so mentioned it to the guide, who asked if we’d been using the mummy sacks correctly. Well, silly us! We assumed correct usage entailed inserting oneself into the sack. Before bed that night he led us through what we called Mummy Sack Seminar 101, the salient points of which were that the head covering attached to the sack is actually there to cover your head and not to be scrunched up into a makeshift pillow, the various bits of Velcro are actually supposed to attach to other bits of Velcro, and that you are better off wearing just one layer of Capilene at night. Why expend your own body heat warming up layers of clothing, as we had been doing, when proper insulation is all that is needed?

RestroomWe were feeling even more challenged by the time we crawled out of them the next morning, because neither of us had slept well, due to the cold. If this was a problem at 9,000 ft., we dreaded to think how we would do at 19,000 feet, so mentioned it to the guide, who asked if we’d been using the mummy sacks correctly. Well, silly us! We assumed correct usage entailed inserting oneself into the sack. Before bed that night he led us through what we called Mummy Sack Seminar 101, the salient points of which were that the head covering attached to the sack is actually there to cover your head and not to be scrunched up into a makeshift pillow, the various bits of Velcro are actually supposed to attach to other bits of Velcro, and that you are better off wearing just one layer of Capilene at night. Why expend your own body heat warming up layers of clothing, as we had been doing, when proper insulation is all that is needed?

However, although clearly deficient in camping experience, we were to discover that we did have one sizeable advantage when our guide took the two of us aside and commented that we would probably have an easier time on the climb than the others in the group. Before we could congratulate him on his ability to recognize superb physical specimens when he saw them he continued with what he wanted to say: “...because you are old, and your brains have shrunk.” He meant it kindly, and his logic seemed reasonable; the brain does contract as it ages but the cranium doesn’t, and at high altitudes this is a positive boon because there is lots of spare room for the swelling that can occur. We’ve since met several doctors who dismiss his theory, but he had led hundreds of people up Kilimanjaro and detected a pattern; they had not. (A piece of advice to anyone considering climbing Kilimanjaro: Give your brain every chance to shrink, and wait until the last possible moment to attempt the climb.)

The next morning a new item was added to our routine. The bottled water we had brought with us had by now run out; from here on we would be dependent on Kilimanjaro’s own supply. None of that is drinkable as is, so every morning we would get our ration from the cooks, which we would then have to treat. The cooks would thoughtfully use a strainer when pouring the water into our bottles, thus extracting at least the larger chunks of foreign matter - twigs, branches, stones, and the like. Next we dropped in two iodine tablets, waited three minutes, turned the bottle upside down, unscrewed the lid and let some water pour out to decontaminate the screw thingies at the top. Then after another 20 minute wait we added a scoop of orange Gatorade. All of this in order to get a simple drink of water. And things only went downhill as we went uphill; as we got closer to the summit the only water available was melted glacier ice - a drink of such opacity, mineral content and general foulness that only repeated warnings about the potentially fatal effects of high altitude sickness could induce any of us to suck it down. We actually reached the point where choosing between the risk of a pulmonary edema and taking one more sip of glacier water was a tough call. Not only that, drinking copious amounts of water carries with it the nagging certainty of having to emerge from one’s cocoon at least several times during the night.

Days 2 and 3: Shira Plateau Camp, with Mount Kilimanjaro in backgroundThe next day we hiked over increasingly rocky terrain to Shira Plateau, at 12,950 ft. A fierce hailstorm greeted us there, but once the weather had got that little outburst out of its system, the porters built what would be our last campfire; we had reached the upper limit of supplies of firewood. We made the most of it, and drifted off to sleep that night to the haunting contrapuntal strains of one of the hikers, a classical percussionist, performing familiar American oldies, and a group of porters replying with their own Tanzanian favorites. The moon was almost full, and it bathed the entire plateau, and Kilimanjaro itself, in an unearthly blue light. Millions of stars were almost within reach overhead, and the frost on the ground sparkled and crackled as you stepped on it.

Days 2 and 3: Shira Plateau Camp, with Mount Kilimanjaro in backgroundThe next day we hiked over increasingly rocky terrain to Shira Plateau, at 12,950 ft. A fierce hailstorm greeted us there, but once the weather had got that little outburst out of its system, the porters built what would be our last campfire; we had reached the upper limit of supplies of firewood. We made the most of it, and drifted off to sleep that night to the haunting contrapuntal strains of one of the hikers, a classical percussionist, performing familiar American oldies, and a group of porters replying with their own Tanzanian favorites. The moon was almost full, and it bathed the entire plateau, and Kilimanjaro itself, in an unearthly blue light. Millions of stars were almost within reach overhead, and the frost on the ground sparkled and crackled as you stepped on it.

Day 2: En route to Shira Plateau Camp, with signs of an earlier forest fireWe were to spend two nights at 14,800 ft. to give our bodies a chance to acclimatize. It was sunny and warm when we set out, but by the time we got to the camp we had hail, snow and sleet to contend with. Dinner that night was a cheerless affair. Despite the cooks’ best efforts, a certain sameness was beginning to creep into the diet - soup, pasta and vegetables being the staples. The novelty of the mess tent was wearing off, too. It was just big enough for six of us on each side, plus the guide, perched precariously and uncomfortably on three-legged camp stools. It zippered shut at each end, but to be seated at either end meant suffering an icy blast each time the tent was unzipped to allow another dish to be passed in. At the same time, to purposely avoid sitting at the end demonstrated poor sportsmanship, and most of us took the rough more or less with the smooth. Two candles on the table did virtually nothing to alleviate the gloom, or shed light on what we were eating. With little appetite, we excused ourselves from the festive board and retired to our tent. But sleep and clarity of thought are hard to come by at that altitude, and to take our minds off the cold, we fell back on one of our staple diversions: Twenty Questions. Our games are always very competitive, and this time it was particularly enjoyable because we could stump one another so easily due to the lack of oxygen in our brains.

Day 2: En route to Shira Plateau Camp, with signs of an earlier forest fireWe were to spend two nights at 14,800 ft. to give our bodies a chance to acclimatize. It was sunny and warm when we set out, but by the time we got to the camp we had hail, snow and sleet to contend with. Dinner that night was a cheerless affair. Despite the cooks’ best efforts, a certain sameness was beginning to creep into the diet - soup, pasta and vegetables being the staples. The novelty of the mess tent was wearing off, too. It was just big enough for six of us on each side, plus the guide, perched precariously and uncomfortably on three-legged camp stools. It zippered shut at each end, but to be seated at either end meant suffering an icy blast each time the tent was unzipped to allow another dish to be passed in. At the same time, to purposely avoid sitting at the end demonstrated poor sportsmanship, and most of us took the rough more or less with the smooth. Two candles on the table did virtually nothing to alleviate the gloom, or shed light on what we were eating. With little appetite, we excused ourselves from the festive board and retired to our tent. But sleep and clarity of thought are hard to come by at that altitude, and to take our minds off the cold, we fell back on one of our staple diversions: Twenty Questions. Our games are always very competitive, and this time it was particularly enjoyable because we could stump one another so easily due to the lack of oxygen in our brains.

Day 3: Shira PlateauThe only thing on our agenda the next day was a short, steep hike on which we would learn the “rest step” technique we would need further up. It’s supposed to be a simple affair of shifting weight and has something to do with combining skeletal and muscular movements. That’s as much as we could fathom. Beyond that we found it impossible to conceptualize, extremely boring, but nevertheless imperative to master if you hoped to keep breathing as you climbed. After giving rest steps our best effort we spent a pleasant afternoon playing Hearts on a sheltered rock. Our percussionist had happily brought some drumsticks with him and he set to work on any and all vessels that resonated - cooking pots, water bottles, and buckets. Before long the porters were either joining in with forks and spoons on plates, or moving sinuously to the rhythm. It was an unforgettable sight: two very disparate cultures brought together in harmony through the common language of music.

Day 3: Shira PlateauThe only thing on our agenda the next day was a short, steep hike on which we would learn the “rest step” technique we would need further up. It’s supposed to be a simple affair of shifting weight and has something to do with combining skeletal and muscular movements. That’s as much as we could fathom. Beyond that we found it impossible to conceptualize, extremely boring, but nevertheless imperative to master if you hoped to keep breathing as you climbed. After giving rest steps our best effort we spent a pleasant afternoon playing Hearts on a sheltered rock. Our percussionist had happily brought some drumsticks with him and he set to work on any and all vessels that resonated - cooking pots, water bottles, and buckets. Before long the porters were either joining in with forks and spoons on plates, or moving sinuously to the rhythm. It was an unforgettable sight: two very disparate cultures brought together in harmony through the common language of music.

Day 7: The Western BreachIn his daily briefing that evening the guide warned us that in that particular location rocks will sometimes come sliding down from above. Should we hear the porters yelling the Swahili word for “Rocks!” at any time during the night (a word which we couldn’t possibly have remembered even at sea level), we were to rush out of our tents and run to the far side of the campsite. He then moved on to what we could expect the next day, should we make it through the night alive. Quite simply, it would be the hardest section of the climb. We would be hiking for about 8½ hours and climbing 2,500 ft., up through the Western Breach and onto the Summit Plateau, which is still below the actual summit. Wake up would be at 5 am, breakfast at 6 am, departure at 7 am, sharp. No excuses. Not headaches, acute mountain sickness, diarrhea, nor any other malady. We had to get beyond the point where the sun could warm the icy rocks sufficiently to cause instability. Furthermore, we should now start keeping anything that could freeze, like batteries or contact lenses, inside our mummy sacks with us at night. Already the mere act of rolling over during the night left you gasping for breath; now we would have the added excitement of hard foreign objects rolling around with us in our sacks. Not wishing to dwell on the perils of the next day, we invited three other climbers to our tent for an evening of games and merriment. Ever the souls of hospitality, we considerately did a little yoga before they arrived in an attempt to warm up the tent with body heat. Not easy in a domed tent barely large enough for two, but on the plus side, there wasn’t much space that needed warming. After they left the temperature dropped noticeably and we donned hats and gloves and shivered ourselves to sleep.

Day 7: The Western BreachIn his daily briefing that evening the guide warned us that in that particular location rocks will sometimes come sliding down from above. Should we hear the porters yelling the Swahili word for “Rocks!” at any time during the night (a word which we couldn’t possibly have remembered even at sea level), we were to rush out of our tents and run to the far side of the campsite. He then moved on to what we could expect the next day, should we make it through the night alive. Quite simply, it would be the hardest section of the climb. We would be hiking for about 8½ hours and climbing 2,500 ft., up through the Western Breach and onto the Summit Plateau, which is still below the actual summit. Wake up would be at 5 am, breakfast at 6 am, departure at 7 am, sharp. No excuses. Not headaches, acute mountain sickness, diarrhea, nor any other malady. We had to get beyond the point where the sun could warm the icy rocks sufficiently to cause instability. Furthermore, we should now start keeping anything that could freeze, like batteries or contact lenses, inside our mummy sacks with us at night. Already the mere act of rolling over during the night left you gasping for breath; now we would have the added excitement of hard foreign objects rolling around with us in our sacks. Not wishing to dwell on the perils of the next day, we invited three other climbers to our tent for an evening of games and merriment. Ever the souls of hospitality, we considerately did a little yoga before they arrived in an attempt to warm up the tent with body heat. Not easy in a domed tent barely large enough for two, but on the plus side, there wasn’t much space that needed warming. After they left the temperature dropped noticeably and we donned hats and gloves and shivered ourselves to sleep.

Day 7: Snowfield on the Western Breach en route to Inner Crater CampWith the preview of coming attractions we’d been given, and the regular effects of our guide’s “Drink, drink” commandment, it’s no wonder that we were wide awake and wired by 4 am. Piling on every layer we owned, we started up the steep trail. It began as scree, but soon we were clambering over large boulders. We could see the crest of the Western Breach above as we climbed, so always knew how much further we had to go. It was a hard slog. "Pole, pole." The thin air was the main enemy; it took at least two deep breaths for every step. Our guide reached the crest well ahead of us, and stood like a beacon in his large yellow jacket, waving his arms and shouting encouragement. He hugged each of us when we got there, probably as relieved as we were.

Day 7: Snowfield on the Western Breach en route to Inner Crater CampWith the preview of coming attractions we’d been given, and the regular effects of our guide’s “Drink, drink” commandment, it’s no wonder that we were wide awake and wired by 4 am. Piling on every layer we owned, we started up the steep trail. It began as scree, but soon we were clambering over large boulders. We could see the crest of the Western Breach above as we climbed, so always knew how much further we had to go. It was a hard slog. "Pole, pole." The thin air was the main enemy; it took at least two deep breaths for every step. Our guide reached the crest well ahead of us, and stood like a beacon in his large yellow jacket, waving his arms and shouting encouragement. He hugged each of us when we got there, probably as relieved as we were.

Furtwangler Glacier near summit of Mount KilimanjaroReaching the summit plateau was like entering a whole new world. The gigantic ice wall of the Furtwangler Glacier, not visible from below, loomed before us. Beyond it, but out of sight, were the concentric triple craters of the volcano, with their ashpits and active fumaroles. They are an extraordinary sight, and we know this only because we bought postcards later that showed them. An optional additional two-hour walk would have taken us to the slopes of the crater, and one week earlier we had agreed that a look at that crater was a must-do detour. Now, at 18,500 ft. and having already climbed for more than eight hours, we could think of nothing remotely interesting about craters, ashpits and fumaroles, but we did think that if we screwed up our determination we stood a fighting chance of making it alive to the tents that had already been set up a few yards away. Later we asked our guide how many people, in all his years of guiding on Kilimanjaro, had gone that extra mile, and were comforted to learn that so far, not one. Self-esteem maintained!

Furtwangler Glacier near summit of Mount KilimanjaroReaching the summit plateau was like entering a whole new world. The gigantic ice wall of the Furtwangler Glacier, not visible from below, loomed before us. Beyond it, but out of sight, were the concentric triple craters of the volcano, with their ashpits and active fumaroles. They are an extraordinary sight, and we know this only because we bought postcards later that showed them. An optional additional two-hour walk would have taken us to the slopes of the crater, and one week earlier we had agreed that a look at that crater was a must-do detour. Now, at 18,500 ft. and having already climbed for more than eight hours, we could think of nothing remotely interesting about craters, ashpits and fumaroles, but we did think that if we screwed up our determination we stood a fighting chance of making it alive to the tents that had already been set up a few yards away. Later we asked our guide how many people, in all his years of guiding on Kilimanjaro, had gone that extra mile, and were comforted to learn that so far, not one. Self-esteem maintained!

That night the temperature dropped in lockstep with the sun, and the wind began to redouble its efforts. Dinner had acquired a new gastronomic fillip, in that both soup and pasta were now being made with the aforementioned glacier water, and it was not an improvement. In fact, about the only positive note about the coming night was that it promised to be a short one: wake up at 4 am with a 6 am in-the-dark departure. Even our guide didn’t get much sleep; during the night he walked around the tents to monitor our breathing, and had oxygen and a decompression chamber in case either was necessary. Latrine excursions had now been replaced by boulder excursions; the modesty canvas around the latrine had blown down during the night, but by then no one really cared anyway. Again the almost full moon was working its magic, lighting the entire plateau on which we were camped, and bathing the immense wall of the glacier in an eerie, icy blue light. It really felt like the edge of the world.

The next morning was bitterly cold. At breakfast someone asked exactly how cold, and a rugged ex-Marine in the group needed no thermometer to answer that; drawing on all the richness of the language of Shakespeare and Milton, he summed it up thus: “F------ cold.” In fact it was -4° F. inside the mess tent, and that didn’t take into account the wind, which, as mentioned, was blowing the camp to bits. Our guide estimated it to be about -20° F. with the wind chill factor, and said that on a scale of one to ten, for conditions he’d known at that camp (ten being the worst), that night rated a nine.

The summit of Kilimanjaro, Uhuru Peak (Uhuru means “freedom” in Swahili), was now at the top of the sheer wall against which we were camped. Again wearing everything we owned and with our headlamps, we switchbacked our way up, “pole, pole,” rest-stepping all the way, and briefly admired a glorious sunrise. At the top we still had to negotiate an expanse of jagged, triangular-shaped ice formations before reaching a simple wooden sign that read:

CONGRATULATIONS

YOU ARE NOW AT

UHURU PEAK, TANZANIA, 5895 AMSL.

AFRICA’S HIGHEST POINT

WORLD’S HIGHEST FREE-STANDING MOUNTAIN

ONE OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST VOLCANOES

WELCOME

We were all euphoric, hugging each other and taking pictures. One man in our group tried and failed to light the celebratory Cuban cigar he had brought up with him for just that moment; he hadn’t factored the wind into his planning. The fabled view of Africa spread out below us wasn’t all that the promotional brochure had promised; it had been pre-empted by thick clouds, with only here and there another peak poking through. How did the two of us feel about having achieved such a goal? Ellie only remembers feeling triumphant, and wanting to linger on the summit. Suzy only remembers feeling cold, and wanting to start down as soon as possible.

Descent to Barafu Hut, with EllieOur descent via the Mweka route was direct and brutal. How anyone makes it up that route is a mystery. We passed a few climbers doing it, and several of them looked nearly catatonic. We ourselves slipped and slid over first rocks and scree, then heath and moor, and finally into forest - a 10,000 ft. descent in 7½ miles. Our only pause was to be a picnic lunch at the Barafu Hut - a prospect that conjured up visions of coffee? Soft drinks? Even beer? Anything would have been a welcome change from glacier water. But no, the hut was a grim unfurnished structure that offered some shelter but nothing more.

Descent to Barafu Hut, with EllieOur descent via the Mweka route was direct and brutal. How anyone makes it up that route is a mystery. We passed a few climbers doing it, and several of them looked nearly catatonic. We ourselves slipped and slid over first rocks and scree, then heath and moor, and finally into forest - a 10,000 ft. descent in 7½ miles. Our only pause was to be a picnic lunch at the Barafu Hut - a prospect that conjured up visions of coffee? Soft drinks? Even beer? Anything would have been a welcome change from glacier water. But no, the hut was a grim unfurnished structure that offered some shelter but nothing more.

We stumbled into Mweka, our final camp, in the late afternoon, having been going since 4 o’clock that morning. Better luck awaited us there. Beer was available, although the camp is 3,500 ft. above the nearest road. We saw crates of empty bottles being carried down on heads, and it was sobering to assume that full bottles had come up by the same method. But sobriety was not uppermost on anyone’s mind just then. Add to that fresh tilapia (also run up from below) in lieu of pasta on the dinner menu, the availability of bottled water, and the knowledge that this was to be our last night of mummy sacks - and all in all the general atmosphere was one of celebration.

Day 9: Descent from last camp to Mweka GateThe next morning, happy in the knowledge that mummy sacks and glacier water had now been consigned to history, as far as we were concerned, we set off jauntily for what we thought would be a quick run down to Mweka Gate, the park entrance, 3,500 feet below us. The euphoria was premature and short-lived. Almost immediately we encountered an old acquaintance - el Niño. The path had been described as “straightforward, but steep in places, and slippery if wet.” The “if wet” caveat proved to be a huge understatement; we were soon ankle-deep in thick mud, negotiating roots and rocks while going steeply downhill. Before long knees and quads were screaming for mercy, and we were whining like five-year-olds to any guide who would listen: “How much longer? You promised it would only be three to four hours!” To which came the heartless reply: “Yes, but not at the pace you’re going!” But eventually, five and a half hours later, we staggered into the small compound at the park entrance, piled into jeeps, and were on our way back to a world full of oxygen and creature comforts.

Day 9: Descent from last camp to Mweka GateThe next morning, happy in the knowledge that mummy sacks and glacier water had now been consigned to history, as far as we were concerned, we set off jauntily for what we thought would be a quick run down to Mweka Gate, the park entrance, 3,500 feet below us. The euphoria was premature and short-lived. Almost immediately we encountered an old acquaintance - el Niño. The path had been described as “straightforward, but steep in places, and slippery if wet.” The “if wet” caveat proved to be a huge understatement; we were soon ankle-deep in thick mud, negotiating roots and rocks while going steeply downhill. Before long knees and quads were screaming for mercy, and we were whining like five-year-olds to any guide who would listen: “How much longer? You promised it would only be three to four hours!” To which came the heartless reply: “Yes, but not at the pace you’re going!” But eventually, five and a half hours later, we staggered into the small compound at the park entrance, piled into jeeps, and were on our way back to a world full of oxygen and creature comforts.

Ellie and Suzy at Mweka GateAll that remained was to mull over the question, why climb Kilimanjaro? Why did two thoroughly contented urban matrons feel the need to punish themselves like that? We had certainly asked ourselves that many times during the long, cold watches of the night, but our brains had been too oxygen-deprived to come up with any good answers. Back at home it came into clearer focus: we had to climb Kilimanjaro because it’s the highest mountain in the world that we could possibly climb, and that made it irresistible to us. The fact that it would become less doable every year trumped an innate tendency on the part of one of us towards procrastination, and so we signed on. We’re glad we won’t have to climb it again, but had we not done it, we would have regretted it for the rest of our lives.

Ellie and Suzy at Mweka GateAll that remained was to mull over the question, why climb Kilimanjaro? Why did two thoroughly contented urban matrons feel the need to punish themselves like that? We had certainly asked ourselves that many times during the long, cold watches of the night, but our brains had been too oxygen-deprived to come up with any good answers. Back at home it came into clearer focus: we had to climb Kilimanjaro because it’s the highest mountain in the world that we could possibly climb, and that made it irresistible to us. The fact that it would become less doable every year trumped an innate tendency on the part of one of us towards procrastination, and so we signed on. We’re glad we won’t have to climb it again, but had we not done it, we would have regretted it for the rest of our lives.

Click here to see a gallery of the photos