MOROCCO: A CAUTIONARY TALE: 2002

Saturday, March 7, 2015 at 04:23PM

Saturday, March 7, 2015 at 04:23PM

Only after we had returned home did we realize that we had gone to Morocco for all the wrong reasons. Most people love Morocco. We suspect that they fall into one of two groups: they have either been jetted in by Concorde courtesy of Malcolm Forbes for his extravagant birthday bash, or they have paid their own way into 5-star hotels, out of which they never venture without an escort whose sole purpose it is to keep them safe and happy. Their excursions into the souks are probably carefully orchestrated, or if they go on their own, they must be very good at signaling their determination to not buy whatever they have stopped – or even slowed down - to look at.

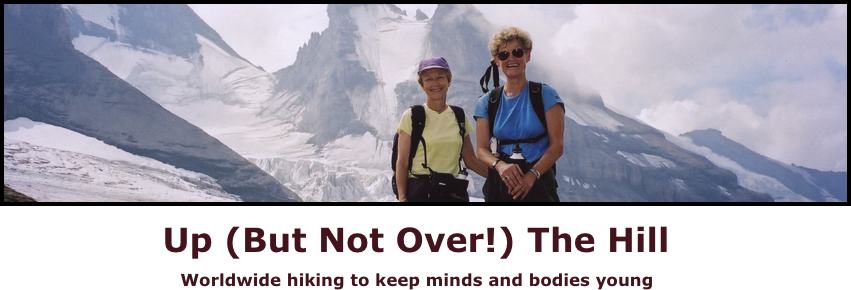

Suzy and Ellie enjoying some warm Gatorade

Suzy and Ellie enjoying some warm Gatorade

We did not love Morocco. We were lured there by Mount Toubkal – North Africa's highest, and another summit to add to our short but growing list. We found a trip that was billed as part "cultural adventure" and part 6-day trek, thus fulfilling our self-imposed requirements. It seemed like a good destination. We had enjoyed the film "Casablanca" every time we'd watched it. Marrakech had an exotic ring to it. And the elevation of the High Atlas Mountains, in which we would be hiking, suggested cool temperatures. All of those turned out to be very poor reasons to go. Two good things did come out of our trip, however. We learned to read trip notes carefully and cynically. And we were able to supply our friends with lots of Schadenfreude when relating the horrors of it all. Even now, many years later, they will murmur "like Morocco?" when pointing out that things could get worse.

We set out for Casablanca with high hopes that were almost immediately dashed by the failure of our luggage to make it that far. Ellie expects luggage to be lost, and packs a carry-on suitcase that has everything she could possibly need to survive until reunited with her somewhat smaller checked bag. Suzy has a sunnier outlook on life, and is genuinely surprised when she finds herself without the usual required articles of maintenance, such as spare contact lenses, comfortable shoes, and, in the case of Morocco in August (average daytime temperature 95°), summer clothes. And in the perverse way that these things happen, Ellie's luggage arrived the next day; Suzy's only caught up with her in Fez, several scorching days later.

Despite that, we spent a pleasant evening in Casablanca, enjoying a memorable shrimp dinner in an unlikely-looking but highly recommended restaurant. Afterwards we watched a Moroccan wedding procession snake its way around the medina, complete with horse, cart, presents, horns and drums, but no bride or groom that we could see.

The next morning we met our guide and group and set out by van on the "cultural adventure" part of the trip. First Rabat, where there was some good sightseeing, and then Fez, with a stop along the way to tour Volubilis – an impressive Roman ruin, but best seen under a less hot sun, if possible.

Volubilis

Volubilis

After Beni Mellal we transferred to Land Rovers and bumped our way to the village of Aït Imi. There our run of comfortable hotels came to an end; we were to spend the night in a gîte – a typical Berber house that had been turned into a guesthouse. It featured a large central room with narrow ledges running around the walls on all sides, and on these we arranged our sleeping bags for the night. Bathroom fixtures underwent an ugly transition, too, with porcelain giving way to holes in the ground. We broke out a deck of cards and played by candlelight, trying to postpone bedtime preparations as long as possible and reminding ourselves over and over that we hadn't come to Morocco to enjoy luxury.

We had come to Morocco to trek and climb, and that was what we were about to do. Our group had now expanded to include several cooks and their helpers, and a number of muleteers in charge of the mules that were to carry our tents and supplies. Ah, mules.

Campsite with mules

Campsite with mules

To be fair, they had been mentioned in the trip notes, but we had failed to read into that fact all the ramifications that we should have. We hadn't counted on them being our constant and proximate companions, wandering among the tents at will. Ours were the fortunate owners of very efficient digestive systems, which added an element of risk to nighttime excursions for us, and produced a veritable feeding frenzy for billions of flies by day. Unwilling to leave such a dependable source of food, flies too were to be our constant companions.

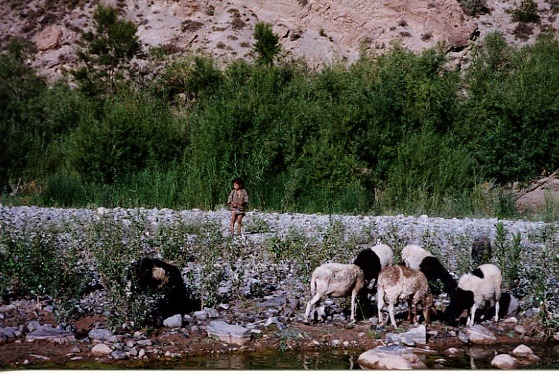

We set out from Aït Imi on foot the next morning, first along potato fields and orchards, and then past small Berber villages of mud huts. Men and women were working in the fields, performing their gender-defined tasks. There were children everywhere - handsome but dirty - begging insistently for pencils or candy. Our guide had warned us ahead of time that to give them anything would be "culturally demeaning" to them, so we did as we were told, trying to get our point across to them with a friendly but firm "la" (Arabic for "no"). Unfortunately, most of them seemed to assume that we were speaking French, and that our "là" meant "over there," so they tagged along tirelessly in the expectation that something good awaited them "over there."

Child

Child

We reached our campground, an azib or high pasture, in time for lunch. That meant we were making good time, but it also meant that there would be little to do in the sweltering heat except wait for dinner and wage a hopeless war against the swarming flies. It is no exaggeration to say that even on this, our first day of hiking, monotony was beginning to set in. The relentless heat made us feel like we were hiking in a tanning salon. Determined flies. The uninterrupted dry and rocky landscape. Long afternoons under canvas (natural shade was almost nonexistent). Drinking powdered Gatorade mixed with warm water. Or, after the Gatorade ran out, simply drinking warm water. (Caveat: it is not a thirst quencher.) Dodging mule pats. The "friendly Berber villages” touted in the literature were clusters of mud houses with seldom a person in sight, except for the one night when some kind of celebration was taking place.

Berber woman near the M'Goun GorgeWe were camped near enough to hear the merrymaking, and it went on long into the night. When it finally showed signs of winding down donkeys picked up the refrain; when they called it quits, the dogs took over; and when even they decided enough was enough, it was time for the roosters.

Berber woman near the M'Goun GorgeWe were camped near enough to hear the merrymaking, and it went on long into the night. When it finally showed signs of winding down donkeys picked up the refrain; when they called it quits, the dogs took over; and when even they decided enough was enough, it was time for the roosters.

By Day Six, the monotony had given way to desperation, and we sat mutinously in our tents at night, trying to figure out a way to escape, make our way to Paris, and happily kill the time there awaiting our flight back to Washington. This plan had virtually no chance of success, stuck as we were in the Atlas Mountains with neither cell phones nor internet access, but the mere fantasizing helped us maintain our sanity.

To be fair, there were some good moments. On one day we hiked through the dramatic rock formations of the M'Goun gorge. The gorge, carved out by the M'Goun River, is only ten feet wide in places, with sheer walls rising more than 4,000 feet on either side. We waded across the river countless times over the course of two days, the cold, shallow water offering some welcome relief from the heat. There was one other day when spectacular scenery was promised, but unfortunately that day coincided with a sandstorm.

M'Goun GorgeAfter what seemed like an eternity we climbed out of our tents for the last time, hopped aboard a waiting Land Rover, and headed down and out of the mountains, en route to Marrakech. There a very comfortable hotel awaited us, with all the conveniences, including the porcelain that we really feel entitled to, however much we try to deny it. We felt euphoric. The euphoria went to Ellie's head, and after a visit to the souk the next day she found herself in possession of a rug she didn't need, and at price she shouldn't have paid, and of such bulk that it was impossible to foresee how she would get it back to Washington. But it came with a detailed pedigree (verbally delivered by the rug merchant, and including something to do with its having been part of a priceless antique dowry), and in purchasing it she doubtless made an entire Moroccan family equally euphoric.

M'Goun GorgeAfter what seemed like an eternity we climbed out of our tents for the last time, hopped aboard a waiting Land Rover, and headed down and out of the mountains, en route to Marrakech. There a very comfortable hotel awaited us, with all the conveniences, including the porcelain that we really feel entitled to, however much we try to deny it. We felt euphoric. The euphoria went to Ellie's head, and after a visit to the souk the next day she found herself in possession of a rug she didn't need, and at price she shouldn't have paid, and of such bulk that it was impossible to foresee how she would get it back to Washington. But it came with a detailed pedigree (verbally delivered by the rug merchant, and including something to do with its having been part of a priceless antique dowry), and in purchasing it she doubtless made an entire Moroccan family equally euphoric.

In Marrakech we fulfilled all the requirements on any basic tourist checklist. We toured a ruined palace and visited a museum featuring wooden objects of dubious interest. In the medina we saw the snake charmers and fire eaters. We tried to dodge the young henna artists who moved in swiftly to begin work on any exposed skin before one had a chance to decline their services. We were introduced to a vast array of herbal remedies that promised relief from almost any imaginable affliction. We were assaulted mercilessly by vendors. That evening we lounged on low banquettes to enjoy a good meal of pigeon in crepes, lamb tajine with tomatoes, onions and cinnamon, and couscous with seven vegetables. Musicians played as we ate and a belly dancer appeared and went through her routine.

The next morning it was time to focus on our main objective: Mount Toubkal. A somewhat diminished number of us pried ourselves away from the short-lived luxury and set off on a four-hour ride in a 4x4 over stomach-churning ruts. Our destination was Imilil, the jumping off point for the ascent of Toubkal.

Imilil

Imilil

Unlike Marrakech, Imilil is well off the beaten track, and we found it more interesting and authentic. Our room in the "best available" hotel overlooked the short main street. Tiny shops lined either side. Directly opposite our window was an old man on a balcony turning out doughnuts. A steady stream of customers carrying pails waited patiently to collect their daily supply as fast as he could fry them.

We set off early the next morning, steeply upwards. Imilil is at 5,576 feet above sea level, and we needed to get to our base camp at 10,332 feet. On the first part of the climb we passed pilgrims, many of whom were heavily shrouded women, on their way to a marabout, or shrine, a few hours up the mountain.

Campsite on way to Mount Toubkal

Campsite on way to Mount Toubkal

By the time we reached the base camp area all the campsites on flat ground had been claimed, and we were left to pitch our tents and perch on a precarious plane next to a steep drop. It made for fitful sleeping and gave an added dimension to nighttime excursions. From there the next day we battled our way over rocks and scree to the summit of Toubkal (13,644 feet), where we were underwhelmed by the views, overworked by the effort to get there, and depressed by the prospect of having to spend another night clinging to the hillside in the base camp on the way down.

But we tried to take the longer view of things: one day later we would be rattling back down the road to Marrakech, boarding a flight for Paris and home, and armed with plenty of material with which to regale anyone who would listen about our travails in the Atlas Mountains.

click here to see a gallery of the photos