New Zealand: Not to be missed (2000)

Getting to the top of Kilimanjaro warrants some kind of a reward, and for us it was taking ourselves to New Zealand the following year. We had never met anyone who didn’t rave about the country, its people, and its white wines. Even if it didn’t promise adventure, we were confident it would deliver pleasure, for which we were eager seekers.

Suzy and Ellie - End of Milford Track

Suzy and Ellie - End of Milford Track

It was a long way to go, so we wanted to be sure we did it justice once we got there, and none of the escorted trips we considered included precisely what we thought we wanted to do, in the amount of time we thought we could spend, and at a price we could afford. Our only solution was to break with tradition and plan the whole trip ourselves. This was at a time when web sites and e-mails weren’t what they are today, but on the positive side, those middle-of-the-night phone calls that we would need to place in order to hit office hours in New Zealand would be answered by English speakers. Or close to it. (There are subtle differences: “miking the beads” has nothing to do with attaching amplifiers to one’s jewelry, but is something you usually do shortly after getting up and brushing your teeth.)

We planned three hikes: the well-known Milford and Routeburn Tracks on the South Island, and the Tongariro Alpine Crossing on the North Island. We arrived with high hopes and expectations, and for the next two weeks they would be exceeded time after time. It’s a glorious part of the world.

The assembly point for both the Routeburn and the Milford Tracks is the town of Te Anau - a fairly long bus ride from Queenstown. If you harbor any doubts as to whether sheep outnumber people in New Zealand, take that bus ride. Deer cannot be far behind the sheep. These were introduced by Scots for hunting purposes, but later a savvy entrepreneur went to Europe and noticed people eating venison. The red deer were domesticated and an industry was born.

Lodge on the Routeburn Track

Lodge on the Routeburn Track

The Routeburn is a three-day, 20-mile guided walk across the Humboldt Mountains, in the Te Wahipounamu South West New Zealand World Heritage Area. (Remembering and spelling the Maori place names is perhaps the most difficult thing about hiking in New Zealand.) The hiking was as challenging and the scenery as dramatic as one might expect in an area called “Fiordland.” The two nights were spent in well-appointed lodges, each with a resident manager. Our guides, friendly young “Kiwis,” would pitch in to help the manager prepare the evening meal, and since the beer and wine poured freely and the walking had been strenuous, we were all sound asleep by 9.30 pm each night. We loved it, and by the third day we were beginning to regret that it wasn’t a longer hike, but we still had other coming attractions.

Routeburn Track: Falls Lodge

Routeburn Track: Falls Lodge

After one day off back in Queenstown, we embarked on the Milford Track. In 1908 this 33-mile walk was described in the London Spectator as “the finest walk in the world,” and if it was good then, it’s even better now that huts have been built along the route. It begins at the head of Lake Te Anau and ends four days later at Milford Sound, justifiably one of the most photographed sights in the world. The walk was pioneered in 1888 by one Quinton McKinnon, a genial Scot, a surveyor and an explorer, who later became a greatly loved guide.

Mckinnon Memorial stoneThe route takes you over Mackinnon Pass, at the top of which stands the Mckinnon Memorial stone. And no, those are not three typos in two sentences, but for us the casual spelling of his name seemed right in keeping with the character of the New Zealanders. Misspellings apparently don’t bother them unduly; missteps do, as we were made aware by our very ecologically conscientious guides. We were enjoined not to disturb any flora and to be very careful where we planted the tips of our walking sticks as we went along. We saw not one scrap of litter on the entire walk.

Mckinnon Memorial stoneThe route takes you over Mackinnon Pass, at the top of which stands the Mckinnon Memorial stone. And no, those are not three typos in two sentences, but for us the casual spelling of his name seemed right in keeping with the character of the New Zealanders. Misspellings apparently don’t bother them unduly; missteps do, as we were made aware by our very ecologically conscientious guides. We were enjoined not to disturb any flora and to be very careful where we planted the tips of our walking sticks as we went along. We saw not one scrap of litter on the entire walk.

Milford Track: Glade House LodgeThe number of people embarking on the Milford Track is strictly controlled during the season. On any given day only forty guided walkers, walking in one direction, and a comparable number of independent or “Freedom” walkers, walking in the opposite direction, are allowed to set out. All must conform to a fixed itinerary and are not permitted to spend more than one night in any one place. The three huts for guided walkers are manned by teams who sign on for the entire season and produce exactly the same dinner and organize exactly the same entertainment, night after night, without fear of boring anyone except themselves. They do have that one meal down to perfection. Provisioning for it is done by helicopter, with large painted graphics on the roofs of the huts showing the pilots whether beef, chicken or fish is to be dropped at that particular location. The evening entertainments include inviting guests to group together and perform a song - any song - representing their particular country. The managers suffer through a lot of “Waltzing Matilda.”

Milford Track: Glade House LodgeThe number of people embarking on the Milford Track is strictly controlled during the season. On any given day only forty guided walkers, walking in one direction, and a comparable number of independent or “Freedom” walkers, walking in the opposite direction, are allowed to set out. All must conform to a fixed itinerary and are not permitted to spend more than one night in any one place. The three huts for guided walkers are manned by teams who sign on for the entire season and produce exactly the same dinner and organize exactly the same entertainment, night after night, without fear of boring anyone except themselves. They do have that one meal down to perfection. Provisioning for it is done by helicopter, with large painted graphics on the roofs of the huts showing the pilots whether beef, chicken or fish is to be dropped at that particular location. The evening entertainments include inviting guests to group together and perform a song - any song - representing their particular country. The managers suffer through a lot of “Waltzing Matilda.”

A KeaA big attraction of the walk was that we were free to set out each morning whenever we felt like it and to walk at whatever pace suited us. There is the one track and no possibility of getting lost. And this being New Zealand, there was nothing to fear in the way of flora or fauna. (Indeed, its total lack of life-threatening creatures was one of the main inducements for one of us.) However, there were caveats, one of which was to beware of the infamous kea.These alpine parrots have mastered the art of breaking and entering to a degree that criminals would do well to study. Shoes, backpacks, anything they can get their beaks and claws onto, are fair game. We never actually witnessed them unzipping things, but were told that it was the work of a minute for them. The only other negative about New Zealand, for us, were the sandflies. These are not a new problem; in 1773 Captain James Cook wrote: “The most mischievous animal here is the small black sandfly which are exceeding numerous and are so troublesome that they exceed everything of the kind I ever met with, where they light they cause a swelling and such an intolerable itching that it is not possible to refrain from scratching and at last ends in ulcers like the small Pox.” And the good Captain was writing with typical British understatement. We might have sensed a warning when, in trying to appease us for a small glitch in scheduling, a woman at the tourist office in Queenstown presented us with huge amounts of citronella. (In our experience, sandflies have adapted themselves to thrive on citronella.)

A KeaA big attraction of the walk was that we were free to set out each morning whenever we felt like it and to walk at whatever pace suited us. There is the one track and no possibility of getting lost. And this being New Zealand, there was nothing to fear in the way of flora or fauna. (Indeed, its total lack of life-threatening creatures was one of the main inducements for one of us.) However, there were caveats, one of which was to beware of the infamous kea.These alpine parrots have mastered the art of breaking and entering to a degree that criminals would do well to study. Shoes, backpacks, anything they can get their beaks and claws onto, are fair game. We never actually witnessed them unzipping things, but were told that it was the work of a minute for them. The only other negative about New Zealand, for us, were the sandflies. These are not a new problem; in 1773 Captain James Cook wrote: “The most mischievous animal here is the small black sandfly which are exceeding numerous and are so troublesome that they exceed everything of the kind I ever met with, where they light they cause a swelling and such an intolerable itching that it is not possible to refrain from scratching and at last ends in ulcers like the small Pox.” And the good Captain was writing with typical British understatement. We might have sensed a warning when, in trying to appease us for a small glitch in scheduling, a woman at the tourist office in Queenstown presented us with huge amounts of citronella. (In our experience, sandflies have adapted themselves to thrive on citronella.)

The first two days were easy walking, partly along the Clinton River and through beech forests. On the third day the going got tougher.There was a small “practice” hill, and then the real thing: Mackinnon Pass. Eleven steep switchbacks, or zigzags, the first six in the forest, and the last five above the treeline, had to be negotiated - some of them during a brief snowstorm. We were fortunate to have in our group another Scot, who always had a wee dram ready for any occasion that merited celebration. He managed to find lots of reasons to celebrate, but standing atop Mackinnon Pass was certainly one of them. And one hates to see a man drinking alone. From that point it was all downhill, 3000 ft. in three hours, to the pretty Quintin Lodge, where we not only had a room to ourselves, but there was a good supply of Speights beer. This had become Ellie’s latest in a long line of favorite beers. Before setting out the next day we spot-checked the lodge’s guestbook. Clearly, with our single short cloudburst we had been extraordinarily fortunate with the weather. Entries read along the lines of “This might have been enjoyable had the rain stopped for even five minutes.” Rain is a fact of life there, but it is by no means a reason not to go.

Milford Track: Arthur River

Milford Track: Arthur River

On the last day there was the option of paying $20 NZ to have our backpacks helicoptered out. It was a negligible amount at that time, thanks to a robust US dollar, and most of our group happily forked over and marched on with a new spring in their steps. One of us would have liked to have done that, too, but the other denounced it as wimpish, and on we trudged for another 13 miles. It was a beautiful walk; wooden walkways had been constructed alongside the river, and cascades and waterfalls tumbled on either side. It would have been equally as beautiful and a lot more comfortable without the backpacks, and this was bitterly noted more than once. As previously noted, the enduring friendship is quite inexplicable.

Milford Track: Between Quintin Lodge and Sandfly PoinAt a spot accurately named Sandfly Point we boarded a small steamer for the short run across the water to our hotel at Milford Sound. And yes, Milford Sound is as unforgettably beautiful as shown in photographs. At least when we were there in 2000 they had succeeded in keeping the human footprint on the area very small; there was one hotel, a backpackers’ lodge, a bar and a cafe, and not a single private house. We hope it will always remain that way, but since change is almost inevitable with the human race, that is just one more reason to boot up and step out to see the world sooner rather than later.

Milford Track: Between Quintin Lodge and Sandfly PoinAt a spot accurately named Sandfly Point we boarded a small steamer for the short run across the water to our hotel at Milford Sound. And yes, Milford Sound is as unforgettably beautiful as shown in photographs. At least when we were there in 2000 they had succeeded in keeping the human footprint on the area very small; there was one hotel, a backpackers’ lodge, a bar and a cafe, and not a single private house. We hope it will always remain that way, but since change is almost inevitable with the human race, that is just one more reason to boot up and step out to see the world sooner rather than later.

Milford SoundOur final hike in New Zealand surpassed our already high expectations of what the country had to offer. We had come across a description of the Tongariro Alpine Crossing quite by chance in a newspaper article, and since we didn’t want to entirely neglect the North Island but had little time left, the one-day, 12-mile “tramp” was perfect for us. We flew to Wellington, rented a car, headed north, and found ourselves in an area of active volcanoes and lunar landscapes. At that time the only hotel in the village of Whakapapa, at the foot of the volcano Ruapehu, was the Chateau Tongariro. We had hoped to stay there, but it was already solidly booked when we had inquired, almost one year earlier. Undaunted, before checking into our decidedly more modest motel in the nearby village of National Park, we paid a visit to the Chateau to see if we could charm them into surrendering a room key. We could not, but it gave us a chance to examine the prominently displayed photographs in the lobby of the most recent volcanic eruption of Ruapehu in 1995 - a spectacular event that narrowly missed engulfing the hotel itself. These must have made a subliminal impression upon Ellie, because at some point during that night an alarm sounded. It was probably only someone’s alarm clock, but to Ellie it signaled an imminent eruption. She leapt out of bed and grabbed her coat and the car keys, desperate to outrun the lava, only to be stopped short by the realization that she had no idea how to drive on the left side of the road. Meanwhile Suzy, showing no interest in self-preservation, waited patiently in her bed for the hysteria to subside so she could get back to sleep. (Ellie insists that it be noted, in the interest of full disclosure and saving of face, that there have been several eruptions of Ruapehu since then; “active” being the operative word.)

Milford SoundOur final hike in New Zealand surpassed our already high expectations of what the country had to offer. We had come across a description of the Tongariro Alpine Crossing quite by chance in a newspaper article, and since we didn’t want to entirely neglect the North Island but had little time left, the one-day, 12-mile “tramp” was perfect for us. We flew to Wellington, rented a car, headed north, and found ourselves in an area of active volcanoes and lunar landscapes. At that time the only hotel in the village of Whakapapa, at the foot of the volcano Ruapehu, was the Chateau Tongariro. We had hoped to stay there, but it was already solidly booked when we had inquired, almost one year earlier. Undaunted, before checking into our decidedly more modest motel in the nearby village of National Park, we paid a visit to the Chateau to see if we could charm them into surrendering a room key. We could not, but it gave us a chance to examine the prominently displayed photographs in the lobby of the most recent volcanic eruption of Ruapehu in 1995 - a spectacular event that narrowly missed engulfing the hotel itself. These must have made a subliminal impression upon Ellie, because at some point during that night an alarm sounded. It was probably only someone’s alarm clock, but to Ellie it signaled an imminent eruption. She leapt out of bed and grabbed her coat and the car keys, desperate to outrun the lava, only to be stopped short by the realization that she had no idea how to drive on the left side of the road. Meanwhile Suzy, showing no interest in self-preservation, waited patiently in her bed for the hysteria to subside so she could get back to sleep. (Ellie insists that it be noted, in the interest of full disclosure and saving of face, that there have been several eruptions of Ruapehu since then; “active” being the operative word.)

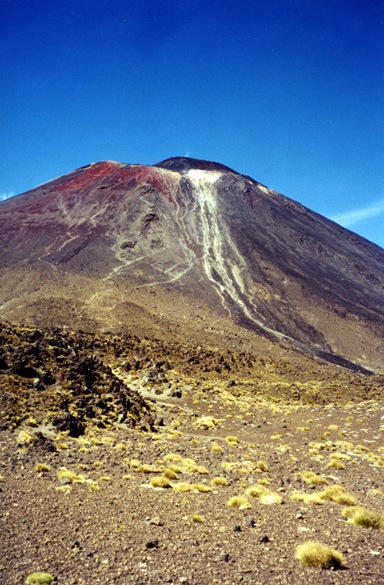

Tongariro Crossing: Mount NgauruhoeA bus circulated among the motels early the next morning and took walkers to the trailhead. Some were doing the same one-day walk that we were; some were headed on more challenging circuits of the area. The bus driver gave us some very important advice and warnings, but in such a strong New Zealand accent that we could not understand much of it. We did glean that it was crucial to be at the pick-up point at the end of the walk in time for the last bus if we didn’t want to be stranded there for the night. And his second admonition, as he looked straight at the two of us, was that a side trip to climb Ngauruhoe would almost guarantee missing that bus. This was disappointing. Ngauruhoe is a picture-perfect volcano that more or less beckons one to clamber up and peer down into it. We could see the tiny figures of a few people doing that. But the sides are steep, about 45°, and a fall, once begun, could last quite a long time. So, reluctantly, we let discretion be the better part of valor. That was fortunate for us; we were so mesmerized by the surreal beauty of the area that we lost all track of time, and later had to almost sprint down 3000 feet of descent, knees screaming for Ibuprofen and brains insisting that we keep going, before collapsing on a bench at the bus stop at the end of the Crossing.

Tongariro Crossing: Mount NgauruhoeA bus circulated among the motels early the next morning and took walkers to the trailhead. Some were doing the same one-day walk that we were; some were headed on more challenging circuits of the area. The bus driver gave us some very important advice and warnings, but in such a strong New Zealand accent that we could not understand much of it. We did glean that it was crucial to be at the pick-up point at the end of the walk in time for the last bus if we didn’t want to be stranded there for the night. And his second admonition, as he looked straight at the two of us, was that a side trip to climb Ngauruhoe would almost guarantee missing that bus. This was disappointing. Ngauruhoe is a picture-perfect volcano that more or less beckons one to clamber up and peer down into it. We could see the tiny figures of a few people doing that. But the sides are steep, about 45°, and a fall, once begun, could last quite a long time. So, reluctantly, we let discretion be the better part of valor. That was fortunate for us; we were so mesmerized by the surreal beauty of the area that we lost all track of time, and later had to almost sprint down 3000 feet of descent, knees screaming for Ibuprofen and brains insisting that we keep going, before collapsing on a bench at the bus stop at the end of the Crossing.

Emerald LakesThe walk is a good 7 to 8 hours over raw volcanic terrain. Anyone who has seen the film, “Lord of the Rings,” will already have a sense of it. In such a monochromatic landscape of loose gray ash it is all the more startling to suddenly come upon vibrant sights like the two Emerald Lakes, the Blue Lake, and the huge and unearthly Red Crater, whose brilliant colors are the result of mineral deposits from past lava flows. There are many active fumaroles, constantly emitting steam and the strong smell of sulfur dioxide, and leaving bright yellow flecks of sulfur around them. Some of these are considered sacred to the native Maoris and are fenced off, with signs requesting that respect be shown and that “pakehas” (non-Maoris) stay away from them. The fumaroles were a visible reminder that we were walking in an area of active volcanoes, and although we tried not to dwell on the fact, it did nevertheless give us a bit of an adrenaline rush.

Emerald LakesThe walk is a good 7 to 8 hours over raw volcanic terrain. Anyone who has seen the film, “Lord of the Rings,” will already have a sense of it. In such a monochromatic landscape of loose gray ash it is all the more startling to suddenly come upon vibrant sights like the two Emerald Lakes, the Blue Lake, and the huge and unearthly Red Crater, whose brilliant colors are the result of mineral deposits from past lava flows. There are many active fumaroles, constantly emitting steam and the strong smell of sulfur dioxide, and leaving bright yellow flecks of sulfur around them. Some of these are considered sacred to the native Maoris and are fenced off, with signs requesting that respect be shown and that “pakehas” (non-Maoris) stay away from them. The fumaroles were a visible reminder that we were walking in an area of active volcanoes, and although we tried not to dwell on the fact, it did nevertheless give us a bit of an adrenaline rush.

Red CraterDespite the fact that the Tongariro Alpine Crossing is a popular walk among New Zealanders, the terrain is so vast that one feels very much alone in it, and very insignificant in comparison with the forces that shaped that landscape. The Maoris have rich legends explaining how it all came to be; other people have different narratives. But however it is expressed, the sense of spirituality that one experiences in a place like Tongariro seems to be universal. And for us, unforgettable. Indeed, the whole country was unforgettable. If we run out of destinations and still have working body parts, returning to New Zealand will be at the top of our list.

Red CraterDespite the fact that the Tongariro Alpine Crossing is a popular walk among New Zealanders, the terrain is so vast that one feels very much alone in it, and very insignificant in comparison with the forces that shaped that landscape. The Maoris have rich legends explaining how it all came to be; other people have different narratives. But however it is expressed, the sense of spirituality that one experiences in a place like Tongariro seems to be universal. And for us, unforgettable. Indeed, the whole country was unforgettable. If we run out of destinations and still have working body parts, returning to New Zealand will be at the top of our list.

Click here to see a gallery of the photos